Lost and Found

Feminism, archives and the university under lockdown

Catherine Grant and Althea Greenan

This text was begun when lockdown had been in place for a couple of months in London. It had become clear that other side of the pandemic was not going to emerge quickly or completely. We wrote to each other whilst thinking about what this meant in relation to work, life, and the university. As curator of the Women’s Art Library (WAL) (Althea), and a lecturer in the Art and Visual Cultures departments at Goldsmiths (Catherine), we discuss how feminist communities and communications might take place through and beyond this period.

Both of us have worked at the WAL: Althea has been a part of the organisation since the early 1980s, whereas Catherine was employed on the magazine published by the WAL between 1999 and 2002. Since then, Catherine has kept in touch with the organisation, cemented by its move to Goldsmiths in late 2002. Our lives at Goldsmiths often overlap, and many of the concerns about the university in this period are issues that are similar to those grappled with over the course of the WAL’s history. We have written to each other with snapshots of our lives as we try and continue to work from home, Althea trawling through the digital assets of a feminist archive whilst remaining in contact with artists and objects being sent in; Catherine trying to speak to students and colleagues on low bandwidth video calls, whilst trying to think about what the university might look like on the other side. The title of this conversation Lost and Found refers to themes that run through the text: how the WAL contains material that is “lost” to mainstream art history, and then “found” again by new generations of artists and writers; the loss of a physical archive or university building, and the finding of new connections online and at home; as well as the general sense of being lost during the early months of lockdown, and having to find a thread that connects what came before and what we might imagine after.

16 June 2020 (Catherine)

How to think about a future when it’s hard to think beyond today; when thinking about more than a few days ahead produces a sense of panic? What is the future we are already living inside of this crisis? I have spoken to friends with very different experiences, as well as students isolating in hotels, hospitals, parents’ houses, and halls of residence. People who are feeling relief that their lives finally slowed down. People slow-walking into debt. People going under with the claustrophobia of being alone, or being with small children all day every day. With migraines brought on by hours on screens, trying to find some way of empathetically connecting through the pixels, whilst inviting back pain as they sit in a corner of a kitchen, bedroom, or living room. What might come out of this that is positive? What can we learn from this intense, visceral isolation? I’ve been trying to think about what the university might look like beyond lockdown, but so far I’m struggling to think of the future. For now, here is a picture of my desk, set up at the beginning of lockdown in an attempt to create a little corner of calm in the face of rising panic.

Image 1: Catherine’s desk, March 2020

22 June 2020, Past the Solstice! (Althea)

The question of communication is everything. I am collecting “stats” relating to emails at my line manager’s request. I‘d like to say it’s because I’m working from home that I need to start counting, but it’s probably more nuanced.

“To be clear,” my lovely manager assures me, “this exercise is to have some key quantitative data for the Library to use (especially since people think we just stamp and shelve books). It's not trying to measure everything we're doing.”

I only count, in other words, the emails that come into my Inbox as unsolicited projects or queries. This is a shame because I’d like to include an email that I have just sent to Holly Argent proposing a kind of mini-project or rather an engagement with a touring exhibition. Holly is the young curator who set up the Women Artists of the North East Library. I want to ask her permission to post her a package of colour photos that came with a note stating that it was an “exhibition” of a single artist’s work. This package was sent from Berlin by a friend and although not solicited, I nevertheless enjoyed the experience of this exhibition-in-a-jiffy bag arriving during the monotony of lockdown. In return for this private viewing, I had to write an email responding to the work directly to the artist. I also had to send the exhibition on to a “friend”, which I was reluctant to do without asking first, because I don’t like anything that sets up those chain letter type scenarios. I can never manage that thing of sending on to another 5 people on pain of – whatever the dreadful consequence would be. DON’T BREAK THE CHAIN is always written in capital letters. I can’t stand it. So I determined to loosen the chain of recipients to include someone who is an ally rather than a friend. Holly Argent first turned up in the Inbox a few years ago to fix a visit to see what women artists of the North East I had in the WAL. Contacting her during this period of working from home is my way of resurrecting the conversations we began over the books, folders and slide files of Rose Frain and others who’d studied at Newcastle. So I emailed her and now wait to see if this idea of receiving an exhibition of a woman artist from Berlin interests her. I wait to see if she consents to receiving this bulky white jiffy bag. I’ll be very glad if she does, for although it is not as satisfying as fetching a stack of boxes, books and folders and putting it down in front of her like a cook putting a meal down in front of a guest, it is a thing! So as I find looking back over email numbers an empty sort of exercise, I hope I get the chance to see what this bag of photos weighs when I take it to the post office and see it off to the North East.

Image 2: Jiffy bag with exhibition from bb.bloc waiting for Holly Argent’s address.

29 June 2020 (Catherine)

The term is finally coming to a close, the whirlwind of zoom calls and webinars, forms to process, essays to grade, all finally slowing to a soft digital murmur. I miss my office at work, and am mostly anxious about what happens next: to the world, and in lieu of any control over that, over the university. What will next year look like, or the next decade? As student numbers seem uncertain, tales of redundancies and non-renewal of contracts circulate. It makes me think back to when the WAL was looking for an institutional home. In early 2000s, finally without Arts Council funding, universities seemed the obvious partner to support what had been an autonomous feminist organisation for nearly two decades. First housed at Central Saint Martins for a brief, turbulent period, Goldsmiths seemed like a safe haven with its Special Collections Room, temperature-controlled storage and room for growth. At the time the contract was signed, we had conversations about which institutions would be the safest location. Which might absorb the material of the WAL into their bigger collection? Which might run out of money? Which would honour their promises to this feminist archive and organisation that was not seen as a priority on the British cultural landscape? When the WAL finally moved I wasn’t working at the organisation anymore, and had not yet begun to work at Goldsmiths. Now we are almost 18 years of WAL being at Goldsmiths, embedded in its Special Collections, and with a thriving programme of artists, curators and writers engaging with its collection that has become newly relevant in the last decade. At the same time, the global pandemic and the marketisation of higher education is making the institution in which it has found a comfortable home seem more precarious than any point in recent history. What might the university look like after lockdown? What are the demands, and how might a feminist archive function within it, as well as feminist academics?

Postscript: I was looking for an interview I did back in the early 2000s to complete some writing. I came across a dictaphone that I had permanently “borrowed” from WAL and a series of interview tapes from that period. Being at home so much is letting me delve into my physical archive whilst my interactions are mostly online. It’s a strange experience that has heightened my sense of time, but also stretched and looped it. The pink sparkly case that I used to carry the dictaphone is a relic of a previous version of myself, another era!

Image 3: Catherine’s personal archive of WAL dictaphone and interview tapes.

Hmmm (VERDANA) (Althea)

I’d like to pause at that question of what does a university look like? From the vantage point of a feminist archive worker in crisis! It’s so interesting to recall the WAL’s move to Goldsmiths which signalled the end of the organisation and the point where it and all its assets were “gifted” to the University. In the eyes of our original “host” university, Central Saint Martins (CSM) – as opposed to the “College” (as Goldsmiths appears in the Deed’s wording) to whom we became the “Donor”[i] – the WAL became a potential liability, so they kicked us out. The WAL’s status at CSM was always murky, if not begrudged, as faculty and students made clear, eyeing the space for studios before we’d even set a leaving date. As I use this working at home time to organise digital documentation from various storage devices, I find the admin files of that year at CSM, evidence of frantic activity but very few collaborations or events with CSM, (the exhibition One Night Stand in the Lethaby Gallery, and the International Women’s Day appearance in the Window Gallery, both CSM venues). When it came to CSM students, we worked best as a refuge. Remember our lovely volunteer, a feminist protégée of Pam Skelton’s with a studio upstairs? And how attached to us she became? I think she volunteered her time amongst the archives for an enhanced education and solace. Being a feminist at art college at that time appeared to be a case of being championed by tutors on 0.5 (at most) contracts and estranged from student peers. To gain a sense of community it was critical for her to have an alternative space in the building to come to and help, participate, even if it was filing an overflowing box file of press cuttings – it was nevertheless a feminist project. I think too, it was a vital extension of studio practice – a space for reflection through doing.

The notion of practice-based scholarship in the arts was just taking hold which is why the launch of the booklet Speaking & Making was an event to celebrate as a feminist project.[ii] And we featured a review in our one and only online version of Make magazine.

Image 4: Screenshot of archived web page from Make magazine web site “...suspended yet constantly mutating” Jon Cairns: Response to Speaking and Making by Joanna Greenhill, Kate Love, Mo Throp, Susan Trangmar

However, this was not a publication looking to the archive as practice, and CSM’s sphere of research remained remote; a city of intrigue from which individuals would occasionally approach but not really connect – and then issue a deadline to leave. The librarians from the main library at CSM weren’t happy, but they were never involved with integrating or working with the WAL or rather Make, the organisation of women’s art, as it was then. The research resource was not what made Make attractive to senior managers at CSM, it was its publication programme, mostly the magazine and the potential of being a kind of edgy artists’ consultancy (never realised). Ultimately no one who wanted us to stay had the power to support us. Everyone at CSM was resigned to the rule of finance, even the Dean.

Image 5: Make, the organisation of women’s art at 109-111 Charing Cross Rd, 2001 photo: Catherine Grant

This image sums CSM up to me. The back door we arrived through and exited from is there. It was always there in that space between the archive and book collections and the magazine offices.

I don’t have any photos of our arrival at Goldsmiths. I remember going up to the top floor of the Library to just look at the collection through the glass walls of the Special Collections stack area, now the Art Journals room (and in the future – what?). Eventually the former Subject Librarian for Art and Design, Jacqueline Cooke carved out a much more ambitious working space on the ground floor for the whole of Special Collections, of which the WAL was by far the biggest and most active. Her vision shaped the WAL’s relationship to the university. That ground floor “suite” as they called it became our means for commoning the WAL – maybe. Once gifted to Goldsmiths the collection began to undergo that process of embedding, and was secured in the Library’s catalogues to gain the long reach into a future of visibility as accessible research material. This repositioning within an institution of Higher Education suggests that the collection had morphed into something that could generate many visions for change rather than producing one as an active arts organisation/publisher.

Maybe this process is a kind of commoning, if I’m reading that Lauren Berlant article you sent round correctly.[iii] This morning, by muddling up the pages, I picked up the text at her concluding argument, which centres on the film In the Air. It documents a town in the US wasteland, depleted of industry, jobs and maybe hope – possibly a vision of our own future economic disintegration that we are bracing ourselves for now. Berlant cites the film to show commons as a verb, and describes how the town’s resource, the young people – in contrast to their disaffected often drunk parents/elders – have this haven, a circus school. And what are they learning? They are unlearning “their defences against each other”, undergoing “a training in attention and also in re-visceralising one’s bodily intuition. It is a training,” Berlant writes, “that collapses getting hurt with making a life [...] There can be no change in life without re-visceralisation. This involves all kinds of loss and transitional suspension.” This reminds me of that kind of physical learning, the repetitive actions between Yvonne Rainer and Wu Tsang that you’ve written about, that does more than teach you something new but somehow how to belong.[iv] Berlant describes our commons as something that has to be socially felt... “The commons always points to what threatens to be unbearable not only in political and economic terms but in the scenes of mistrust that proceed with or without the heuristic of trust.”

So I have no problem seeing where the archive fits in this, even today, as it is suspended between the physical and the digital. For instance, the idea of the hurt that an archive can inflict through revelation. When the artist Samia Malik discovered the Women of Colour Index (WOCI) artists at WAL (a project set up by Rita Keegan in 1987 to map the artists of colour in the WAL collection), it triggered a sense of having been betrayed, kept out of the loop of knowledge, to which she responded vigorously by reproducing that archive and repositioning herself as the teacher by founding the Women of Colour Index Reading Group (https://wocireadinggroup.wordpress.com/). The artist group X Marks the Spot (XMTS) revitalised the WOCI by re-visceralising the knowledge it holds. They sought out people to speak to, record, photograph, draw near to, commission, to add. They stored everything digitally, on Tumblr and that become a commoning of the WOCI. The future of the university lurks here somewhere. A different economy...

Image 6: Cover of Human Endeavour: A Creative Finding Aid for the Women of Colour Index, edited by X Marks the Spot, Joan Anim-Addo, and Althea Greenan, (London: Goldsmiths, University of London, 2015)

The future, feminist university (Catherine)

This idea of a different economy is one that has powered the WAL throughout its existence. It has managed to survive during the 1990s and early 2000s, a period when many grassroots arts organisations floundered, as funding was pulled, and a neoliberal capitalist model just didn’t fit for most. It seems that the university is going through the same transformation: one that is brutal, fantastical, and ultimately will leave many institutions on the rubbish tip of history. The idea of commoning (my auto-correct just changed it to “communing”!) seems essential, but not necessarily easy to understand. When I was thinking about this pre-pandemic, I had the sense of the university being in crisis, but maybe in a slightly different way, and trying to imagine what it meant to be part of that. The ideas I came up with were channelled through Virginia Woolf’s concept of the “new college, the poor college”, set out in her rageful, essential polemic Three Guineas (1938). [v] But I was also inspired by the idea of the “undercommons” proposed by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, a romantic place of “fugitive black study” that includes the kinds of feminist artist-scholars that the WAL has been a refuge for over the years (including Samia Malik, and the members of X Marks the Spot, as you explore above).[vi] Harney and Moten explain that in their idea of the undercommons “we are committed to the idea that study is what you do with other people”[vii] and that the university is not necessary for this, but nonetheless is an “incredible gallery of resources”.[viii] In The Undercommons, there is an argument for a kind of passionate anarchism, a calling into community that is found when the landscape is desolate and unwelcoming.

Returning to Woolf, what I find the most compelling in her argument about “the new college, the poor college” is the way she frames the importance of money in terms of influence and longevity. This is something that I have been thinking about a lot, as my job feels insecure in a way it hasn’t since I finally got a permanent post in the mid 2010s. The pandemic has underlined the inequalities of society, baldly felt through a lack of financial security. As jobs have been lost, people in poorly paid jobs have kept us alive, and the financial logic that our society has been based in is revealed again and again as mercenary and impossible. A decade or more of austerity, along with rising xenophobia, has created a toxic context from which we all need to reimagine our institutions and our communities.

Woolf’s book Three Guineas is framed around three letters that each request money for a different cause. One of them is to support the rebuilding of a women’s college. This leads Woolf to consider what might make a college that encouraged liberty and discouraged war: “Now since history and biography – the only evidence available to an outsider – seem to prove that the old education of the old colleges breeds neither a particular respect for liberty nor a particular hatred of war it is clear that you must rebuild your college differently.” She continues that this new college:

“… is young and poor; let it therefore take advantage of those qualities and be founded on poverty and youth. Obviously, then, it must be an experimental college, an adventurous college. Let it be built on lines of its own. It must be built not of carved stone and stained glass, but of some cheap, easily combustible material which does not hoard dust and perpetrate traditions. Do not have chapels. Do not have museums and libraries with chained books and first editions under glass cases. Let the pictures and the books be new and always changing. Let it be decorated afresh by each generation with their own hands cheaply.”[ix]

This description chimes with some of what the WAL has done: it has built a collection that is “new and always changing”. However, it has not thrown out what has been gathered by previous generations, but instead sought to find ways of making these historical legacies visible, as you have explored. It is often done cheaply though, and with little in the way of expensive infrastructure. Woolf sets out this vision before rejecting it as unfeasible in the face of needing to gain qualifications that are recognised and add to someone’s employability. However the fantasy still remains in her text, the desire to re-imagine the university that can be flexible, dialogical, and creative. She argues that “if the college were poor it would have nothing to offer; competition would be abolished. Life would be open and easy. People who love learning for itself would gladly come there. Musicians, painters, writers, would teach there, because they would learn.”[x] At this moment, when there is a tipping point for universities in terms of finances, some new thinking about how funding is put in place, how inequalities are dealt with in the institution, is newly urgent.

Woolf is responding at a moment of immense change, writing on the eve of the Second World War. At this current moment the pandemic is experienced as a more mute, difficult to articulate form of horror. It is also experienced so differently depending on people’s job, finances, and health. Here I am, tapping away at my keyboard, having tried to maintain a sense of normalcy for my students during a term when nothing has been certain. I have been fortunate to have a salary, to have a flat where I have space to work, to have been ill but recovered quickly, as have most of my family and friends. During this period I haven’t been able to think more than a week ahead, sometimes only a day. At the beginning I had a sense of panic and claustrophobia, as I waited to get ill, waited to get better, waited for my kids to get ill, get better, whilst hearing of colleagues who have died, or in intensive care, as well as the constant updates about shambolic response to the pandemic, shouldered by people who are already exhausted and overworked.

During this time I have found writing almost impossible, and creativity has been replaced by a constant stream of admin. But the questions raised by Woolf as to what this new college might look like remain. There are both conceptual questions and the practical ones. As I learnt from watching the WAL move from autonomous institution to university archive, these questions are intertwined. What happens to our jobs as the university changes? How do we fund the poor college, the undercommons? There needs to be stable funding and stable salaries for the university, the archive, the feminist art library, as a way of ensuring that there is a sense of possibility in the present that is not premised on precarity and hardship (see the discussions on the universal basic income that have arisen during the pandemic).[xi] Otherwise we are always building something from nothing (or on a something that burnt out, had run its course, exhausted the temporary bursaries and short-term funding). We need to make sure we don’t have to return to our kitchen table permanently.

Althea, I loved seeing the pictures you sent of early webpages from Make (the name WAL took for a number of years) and of our days at CSM. In response this is a picture from going online and reading from Gertrude Stein’s epic novel The Making of Americans as part of Irene Revell and Anna Barham’s ongoing series.[xii] Perhaps this is an image of a poor digital university? But what of a poor digital archive?

Image 7: Catherine reading a page from Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1925) as part of Anna Barham and Irene Revell’s project They are all of them themselves and they repeat it and I hear it: a yearlong reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1925)

14th July 2020 (Althea)

Woolf’s reference to a chained library is so fitting. I had never heard of such a thing until I came across one by chance in Dorset in Wimborne Minster at the top of a tight spiral staircase twisting left to disadvantage right-handed weapon-wielding invaders. The library at the top escaped being destroyed during the Reformation, and perhaps this dimly lit space encapsulated in thick stone was exactly what a furtive reader would have needed to relax with the texts. But this space felt sad, with its huge tomes shelved with their bindings facing the wall, each chained to a metal railing. I was not intruding into a space for study; it was more like a bunker of artefacts surviving many human lifetimes and set grimly to outlive many more. Not all preservation enhances our sense of purpose and lends vitality to our relationship with knowledge. So I rejoice in Woolf’s championing the “combustible” structure, disdaining those books on chains or enshrined in glass-cases along with the edifices carved in stone. Since WAL arrived at Goldsmiths bringing groupwork into the archive through artistic, curatorial and writerly interventions, we make the institutional structure more visible and perhaps combustible.

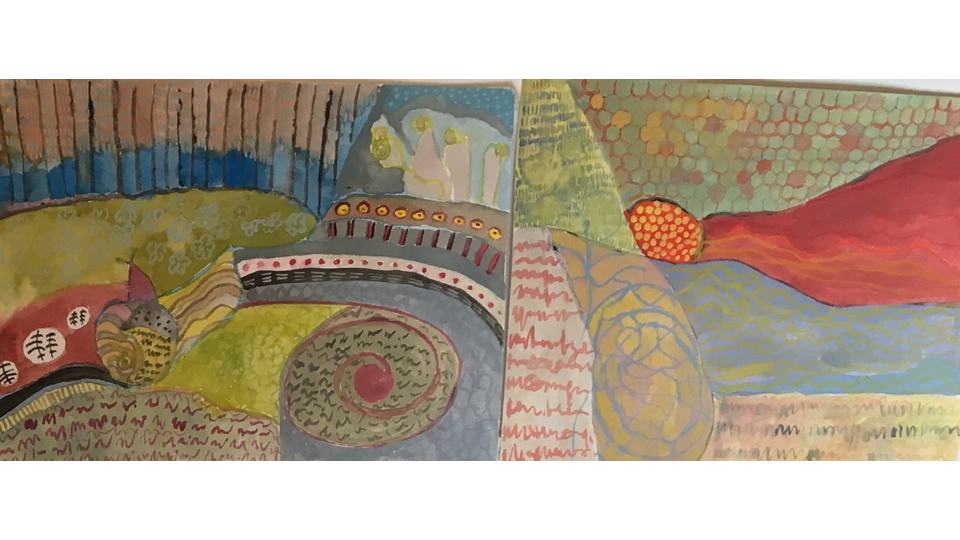

I was struck by a number of points raised in a recent conversation from Bryan Alexander’s Future Trends Forum where he discusses academia, race, and the pandemic with Jessie Daniels, an American professor of psychology who writes extensively on racism in digital spaces.[xiii] This is a forum concerned with the future of higher education and the discussion kicked off by bringing academia down from the ivory tower or as Daniels put it, “We are not protected from the rest of the world.” COVID highlights the fact that many students, especially Black and POC have experienced trauma and continue to deal with it from day to day, something the academy is “not very good at handling”. COVID not only exposes but makes this inequality of living circumstances more acute by “yanking away” the spaces that universities offer such as the library and the classroom, that should act as sanctuaries for these students. The syllabus and the teaching needs to take the experience of trauma into consideration to enable students to bring their full selves into the learning experience. Critically, Daniels turned to academia as a workplace and the urgent need to make it more empathetic. This includes thinking of our whiteness in the workplace. I know that the WAL has transformed the Special Collections Reading Room into this kind of sanctuary for many students and the work of welcoming is much more supported when groupwork happens there. One student, Gaytri Roopnarine, a postgraduate researcher in Computational Arts, after attending a session on decolonising the feminist archive[xiv] arranged to spend a few hours several times a week in 2019 painting watercolours (I made sure this was possible) in a room usually kept clear of all pens and markers. Leaving electronic devices behind, Roopnarine used pigment, brushes and water to visualise her sense of a university space that she felt was transformed by the women-centred archive.

Image 8: Under the River 1, 2018. Painting by Geeta Roopnarine made in the Special Collections and Archives Study Room, Goldsmiths

Jacqueline explains how collections need to have suggestive power, and reflect on the limitations of the commercially available art documents that constitute the lending library, or Main Sequence where, “...more actions, events and thoughts remain undocumented there” that risked perpetuating “a simplified and reductive version of history to future researchers.” [xv] Just as the WAL collection is a commentary on the Main Sequence of the Library, the Women of Colour Index lay dormant as a commentary on the WAL collection that was given voice under the empathetic as well as attentive groupwork of X Marks the Spot in 2014–2015. They responded to a set of folders of photocopies by building a community of black artists, scholars and an intergenerational group of artists who were brought together by XMTS to recreate the WOCI in the book Human Endeavour: A Creative Finding Aid for the Women of Colour Index.[xvi] The best research in the WAL collection emerges as a dialogue between the archive and the researcher. I see it as an example of how the academy can be valued and reformed, agreeing with Jessie Daniels that the hiatus created by Covid is the opening for thinking collectively especially to relieve the “undue burden” on individuals. In the context of academia, the feminist archive project supports the critical citation practice that has become a named movement Cite Black Women.[xvii]

The digital images we can exchange so easily evoke a kind of intimacy, while the institutional scans made as digital surrogates for items that would otherwise have to be in glass cases also satisfy curiosity / a kind of sensory enquiry. But while the chat over coffee has its own rhythm, the interaction with a box of material too... the digital exchange has the potential for feverish one-sided overload. Like the archive, we need to impose our own rhythms on it and delimit our personal opening hours. How many times have I witnessed researchers abandoning themselves completely to the allure of the archive in the knowledge that I will interrupt them at closing time and break the spell. The WAL is so different to other collections as it demands to be performed, implies gaps in knowledge, and persists as an irritant. The university – the gallery of resources – is also the theatre of performing knowledge where we show each other how to do that. The stage is being restructured to proliferate into many hybrid spaces where the material and the digital can be unpacked and explored and along with this communities of exchange become visible. When we’re bewitched by an archive or inspired by a collective mission, it’s a form of embodiment epitomised in the WAL by a gold lamé mask, gloves and bodysuit that consistently transforms the researcher who is transforming the archive.

Image 9: Nina Hoechtl, Archive box of Superdisidencia.net, 2012

Image 10: Student in Gender, Sexuality and Media module session, March 2017 photo: Rebecca Coleman

14 July 2020 (Catherine)

That seems like the place to leave this conversation: That gold lamé suit, donated to the collection by the artist Nina Hoechtl, when worn by a first-time visitor to WAL (something that both you and I have encouraged many visitors to do!) is an image that seems celebratory, silly and participatory. But it is something that would not happen if WAL wasn’t in the university, if there wasn’t just enough infrastructure for us to have time to do this sharing with various groups of students, artists, academics. The gold lamé suit, waiting in its archival box, contains the elements that I love about universities and feminist art libraries: ways of coming together, moments of surprise and learning, as well as an historical record. I guess we both see this as being the future of the university – how to make sure we have just enough resources to let there be spaces of play. To make sure that we have enough autonomy to allow collaboration and re-imagining to take place inside of the institution, to shape its future. What these look like in the digital realm is something we are both starting to figure out. I’m looking forward to it.

References:

[i] Deed of Gift drafted in 2002 between Goldsmith’s College and MAKE Women’s Art Archive (now known by its previous name, the Women’s Art Library).

[ii] Greenhill, Joanna, Mo Throp, Kate Love, Susan Trangmar, Speaking and Making, Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design. London: Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, 2001. Print.

[iii] Lauren Berlant, “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13 May 2016, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989.

This article was circulated by PhD researcher Tom Clark, as part of an online seminar “Thinking Infrastructures// Performing Meetings”, 16 June 2020. Catherine then forwarded the article to Althea.

[iv] Althea is referring to a discussion of the film Salomania (2013) by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, in Catherine Grant, “A Time of One’s Own”, Oxford Art Journal 39, no. 3 (1 December 2016): 357–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcw025.

[v] Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas (1938), (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2014). Woolf repeats this phrase a number of times, see p. 33.

[vi] Some of our friends queried whether the undercommons was the best model for WAL, and suggested that of the ‘para-site’ instead. The undercommons has numerous elements, some of which overlaps with Janna Graham’s description of various ‘para-sitic’ organisations and groups within institutions. See Graham, “Para-Sites like Us: What Is This Para-Sitic Tendency?”, February 2015, http://www.newmuseum.org/blog/view/para-sites-like-us-what-is-this-para-sitic-tendency.

[vii] Fred Moten, “The General Antagonism: An interview with Stevphen Shukaitis”, in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), p. 110.

[viii] Stefano Harney, “The General Antagonism: An interview with Stevphen Shukaitis”, p. 112.

[ix] Woolf, Three Guineas, pp. 32-33.

[x] Woolf, Three Guineas, p. 33.

[xi] For example Hannah Black and Philippe Van Parijs, “Basic Instinct: Hannah Black and Philippe Van Parijs Discuss Universal Basic Income”, 17 April 2020, https://www.artforum.com/slant/hannah-black-and-philippe-van-parijs-discuss-universal-basic-income-82760.

[xii] Anna Barham and Irene Revell, They are all of them themselves and they repeat it and I hear it: a yearlong reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1925) (2020), first begun as physical gatherings and continuing online after the onset of the pandemic. More information can be found here: http://www.annabarham.net/theyareallofthem.html

[xiii] Jessie Daniels, Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights, accessed July 16, 2020, https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780742561588. Daniels maintains the RacismReview blog: http://www.racismreview.com/blog/

[xiv] “Decolonising Translation, Decolonising Feminist Art Archives”, Goldsmiths, University of London, accessed July 15, 2020, https://www.gold.ac.uk/calendar/?id=11384. Workshop organised by Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski with Katherine Carbone (CalArts) and Aida Wilde (Sisters in Print) as part of a Transatlantic Feminist Art Exchange. Ego shared experiences of researching at CalArts for traces of the Women of Colour Index.

[xv] Jacqueline Cooke, “Art Ephemera, Aka ‘Ephemeral Traces of 'alternative Space’ : The Documentation of Art Events in London 1995-2005, in an Art Library’” (Ph.D., Goldsmiths, 2007), http://eprints.gold.ac.uk/3475/.

[xvi] X Marks the Spot, Joan Anim-Addo, and Althea Greenan eds., Human Endeavour: A Creative Finding Aid for the Women of Colour Index, (London: Goldsmiths, University of London, 2015), http://research.gold.ac.uk/19685/.

[xvii] “Cite Black Women”, Cite Black Women, accessed July 15, 2020, https://www.citeblackwomencollective.org/.