Student Spotlight

Spotlights and testimonials from students who have graduated from the Centre for Research Architecture.

Primary page content

Spotlight on Gabriella Demczuk

My name is Gabriella Demczuk and I graduated from the masters program at the Centre for Research Architecture (CRA) in 2022. Before coming to Goldsmiths, I was working in Washington, D.C. as a freelance editorial and documentary photographer. For ten years I covered Washington politics as a member of the White House press, starting with the Obama administration through the Trump years to the beginning of Biden’s presidency, all the while reporting on issues related to immigration and environmental policy across the United States.

It was during this time that I saw the devastating effects of climate change on American communities and the continued environmental injustices of capitalist extraction. Wanting to expand my practice into research, writing, and spatial analysis to dive further into these issues, I joined the CRA after reading about the course in the Guardian. While my start was delayed due to Covid, the wait was worth it to have classes in person as I found the communal learning environment and peer discussions to be the most enriching aspect of the program. The course was split between spatial theory and studio (Research Architecture), creating a balance between research and practice. Through roundtable reviews, live investigations, work in progress presentations, and technical workshops, I learned methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and spatial understandings that coalesced in my dissertation research.

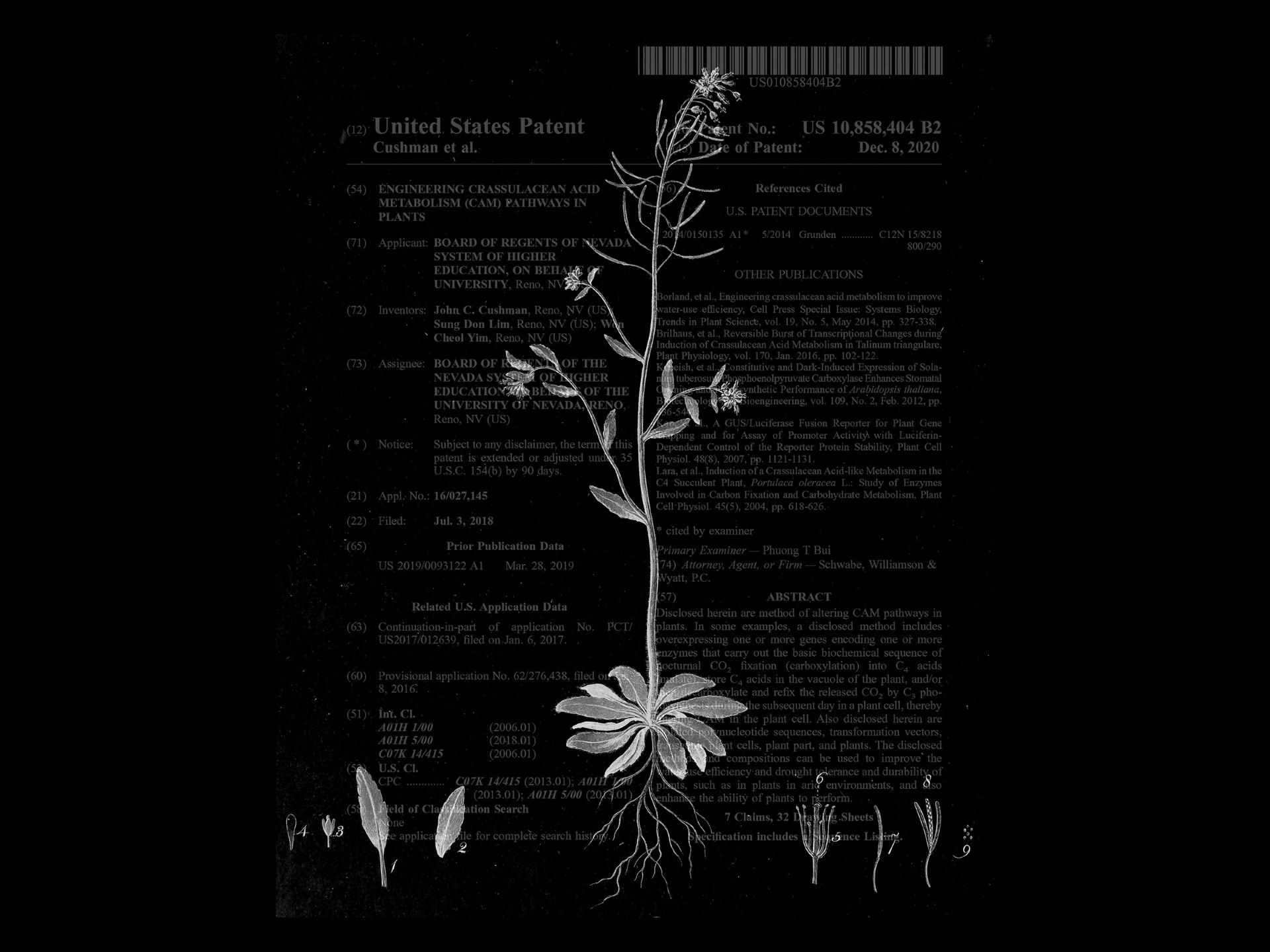

My dissertation focused on biological patents and how they reshaped the landscape of American agriculture. I came into this research worried about technological solutions that promised quick fixes, especially in the emerging field of genetic engineering, and its growing role in ‘fixing’ food insecurity. Biological patents are a form of paperwork that permit the possession of living organisms through proprietary modes of abstraction. This research looked to understand how paperwork abstracts our world and reasons ownership, including biological entities like the food we eat and the plants we tend. With my deep knowledge of American federal governance, I started in Congress, where policy, made concrete through paperwork, opened the door to biological ownership.

I found friendship and commonality in research with two other classmates, Areej Ashhab and Ailo Ribas, coming together after the program to form Al-Wah’at, a research-artist collective. Al-Wah’at seeks to counter harmful anthropocentric and colonial narratives that position arid lands as ‘empty,’ ‘unproductive,’ or ‘waste,’ by engaging with a diversity of knowledges—be they local, scientific, more-than-human— that take into account the material, ecological and social implications of climate change.

Our first case, Wild Hedges, studies the ecological and socio-political complexities of the prickly pear cactus and the cochineal insect across multiple geographies, communities and temporalities, and collectively experiments with the material possibilities of the cactus—in building, weaving and cooking—and of the cochineal—in dye-making and printing—in order to cultivate practices of care around changes in our environments. We started the project through a residency with “Soil Futures” in early 2023, spending nearly two months in Palestine at Sakiya in association with Arts Catalyst. Our ongoing project won the COAL Prize and the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture in its first year, supporting further research over multiple years and geographic regions.

Outside of the collective, I continue my photographic practice, expanding it into different visual methodologies while continuing to research on issues of political ecology, proprietary modes of abstraction, and colonial/capitalist land practices. I currently teach Media Studies in the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art.

I'm Tara Plath and I graduated from the MA Research Architecture program in September 2019. Prior to attending the programme, I had studied fine arts and visual and critical studies, and worked in arts administration and communications for several years before deciding to return to school.

My undergraduate thesis had explored the relationship between the built environment and pictorial representations, drawing from the photography series by Broomberg and Chanarin titled ‘Chicago’ and Eyal Weizman’s accompanying text WALKING THROUGH WALLS – Frontier Architectures, and in this way, I was directed to the work of the Centre for Research Architecture. While I had considered other interdisciplinary programmes at the intersections of art, architecture, urban studies, and critical theory, I ultimately applied to only the MA Research Architecture programme, as it somehow managed to encapsulate everything I was seeking.

I arrived to the programme with a set of goals: to develop my practice as a researcher and produce a body of work that was critically rigorous; to develop relationships with like-minded researchers, who had similar interests in developing research towards political/activist ends; to develop a technical and conceptual skillset that could be of use in activist work; to use the year living outside of the United States as an opportunity to gain perspective on some of the pressing issues occurring inside of the country.

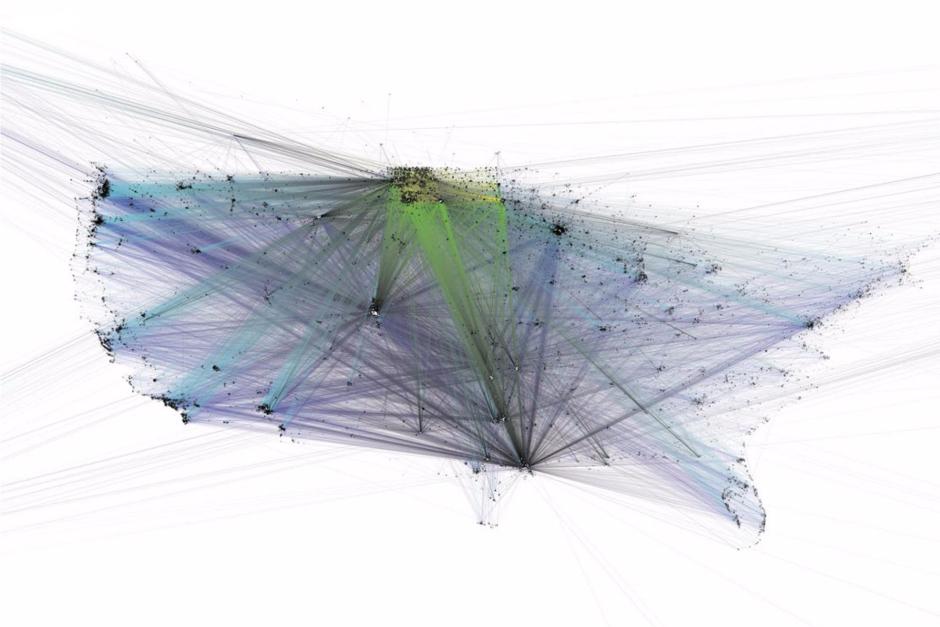

My research soon became focused on the missing persons crisis along the US-Mexico border, primarily on federally managed lands in Arizona’s west desert, where thousands of migrants have died and disappeared as a result of failed U.S. immigration policy and Border Patrol tactics.

In my research, the entangled fields of land management, conservation, ecology, immigration policy, trade deals, and activism, and the criminalization of humanitarian aid were grounded by an intensive investigation of a piece of Border Patrol technology called Rescue Beacons. As the MA is short but intensive, it was useful to direct my research questions and investigative process with these seemingly innocuous objects, which were cited by Border Patrol as an effective solution to the ongoing human rights catastrophe in the region, but of which little data was publicly available.

The investigation required gaining a deeper understanding of the settler-colonial context of the U.S. Mexico Border, by which certain spaces are deemed terra nullis and are put to work as a form of natural border; the politics of mourning and accounting for the dead within the discourse around citizenship, deservedness, and racialized bodies; and the application of humanitarian principals and rhetoric within the deportation regime.

While engaging with these concerns, I began to employ open source investigation techniques, including FOIA requests and the use of satellite image services, in order to geolocate over fifty rescue beacons in the desert. The conceptual and practical concerns at the heart of my research were not distinct from each other but developed in tandem and dependent on the other.

As my research began to take shape, I connected with the humanitarian aid organization No More Deaths/No Más Muertes. The organisation was working on a human rights report that criticised Border Patrol’s role in rescue operations in Arizona. A section of the report was dedicated specifically to Rescue Beacons. This fortuitous overlap allowed my research process to be directed by the needs of this important organization, giving my investigated added urgency and offering a very practical bridge from the incredibly rich discourse that happened at the CRA to an opportunity to mobilize the research for activist ends.

Over the course of the year, I was constructively challenged and encouraged by my peers, Susan Schuppli, and my advisor Lorenzo Pezzani. The wide breadth of experience and perspective offered by cohort was invaluable, as their backgrounds spanned various disciplines and industries but had a shared commitment to developing unique methodologies and modes of critical intervention in spaces of conflict or violence.

The programme culminated only a few months ago, and while I had the opportunity to develop my own practice as a practice-based researcher, it was as valuable to me to establish a collaborative practice with my peers, which will continue to develop in the months and years to come.

Research can be a solitary process, but the work required of us inside and outside of the CRA depends on cooperation, collaboration, and dialogue that expands upon the collective skills and insights we gained while studying together.

My name is Nick Axel and I'm an architect, writer, critic and editor based in Rotterdam. I studied my MA at the Centre for Research Architecture, graduating in 2015. My research and dissertation investigated the deregulation of hydraulic fracturing in the United States through the media of federal history, property rights and land law.

I am currently Deputy Editor of e-flux architecture, which focuses on generating new audiences and experimenting with the temporal logics of the architectural project. Previously, I was the Managing Editor of Volume Magazine (#44–49), where I explored the implications of neoliberal subjectivity, planetary computation and anthropocenic thought on the discipline of architecture. I was also a Researcher at Forensic Architecture, where I coordinated investigations and developed techniques for the inquiry into human rights violations in Palestine and Syria, and I was resident at DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency), where I designed the National Spatial Plan for stone extraction in Palestine.

I have taught architecture, design and theory at Strelka, Design Academy Eindhoven, KABK, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and The Bartlett.

.jpg)

My name is Henry Bradley, and I completed the MA at the Centre for Research Architecture in 2017. In the years after my Fine Art BA, 2010-13 I felt that my practice wasn't developing in a way that allowed my differing interests and ambitions in aesthetic and socio-political areas to come together. It was then that I began to look outside of the traditional Fine Art programmes, consequently stumbling across the Centre online, and instantly finding both its subjects of research and its collaborative ways of working to be pertinent to what I deemed important modes and themes to address in our contemporary climate.

Despite the Centre’s multi-disciplinary focus, it was this relationship to Fine Art, and the fact that fundamentally I wanted to make things, that I think set up a really interesting relationship to the Centre for me. Throughout the two years I was there the one question that stayed with me the whole time was really how to implement this idea of ‘practice-based research’ that the Centre rigorously explores? What sort of knowledge, ideas and relationships can I generate through my visual practice that theory does not offer? And how may those aesthetics and knowledges be able to operate across fields, including the academic, with their varying languages and platforms? How does an artist function in such research settings? Exploring these fundamental questions, pertinent for me and I know many others in CRA, was the core of what really drew me to the Centre.

Throughout my time there the relationships with the people seemed to develop from a collective curiosity about the world, and the ways our practices could potentially function within it. The extremely dedicated teaching staff consistently offer you time to help you to frame, re-frame, to break down and build back up your research, all the while diminishing the barriers between themselves, the PhD’s and the MA students. Alongside this, the collaborative and progressive nature of the educational programme itself lays out the possibilities for relationships to develop beyond your interaction in class settings.

Within my year group, despite our differing practices and interests, there seemed to be a collective desire to try to work out what we were doing in the Centre, and to discover what the collective potential of being and learning together in the Centre could be; there was a real sense of urgency, that we were there together for a year; what could we do? What could it be? This reached its peak with a weekly student-led seminar called ‘Free Seminar’, and a collaborative residency at Arts Catalyst Gallery in Kings Cross. Both of these experiences, as well as many others in the Centre, including the Conflicts and Negotiations course, offered me a massive learning curve in how to work together, one which continues to be invaluable to me and my current collaborations today. Without the students of my year, of whom set up such a great support network with each other, my time at CRA would have been completely different, and a lot of these people I still am working with, or wish to work with today.

Completing the course part-time over two years meant that I was able to engage with courses and groups in the wider Visual Cultures Department in my second year. It was a reading group of Mark Fisher’s ‘Weird and the Eerie’, setup by students and teachers that will really stay with me. Also, the way the students around me acted within his course ‘Post-Capitalist Desire’, as we self-organised and invited guest speakers to each class. It was these experiences, beyond academia, that also helped me to come to terms with my own relationship to anxiety. To see the whole department around you facing the notion of rising mental health in universities helped me to situate my own self into something much larger. All of it showed how close together the Department is, and also how the progressive ideas being spread around have seeped into wider aspects of life, outside of work, for all the people involved.

Turning to my work there, I had always been interested in performance and the body, but it was CRA and the Visual Cultures Department at large that gave me the tools to see this as a complex social and political venture. Performance, and the body, then became embedded within a whole set of social, political and economic power structures. It was here I began to develop an interest in theatre as a critical gaze, offering me a framing device in which to view the subjects of personal and collective discussion in the Centre through. Taking these interests I began my first work with actors there. I started casting, rehearsing and shooting with actors where I could, making my first video work in CRA in February 2017, of which set me up in a great way to then begin the production of my final work.

In the grand scheme of things I really was a complete amateur filmmaker but, with support from Susan Schuppli, I began contacting numerous people, institutions and acting agencies, looking for a way to make something related to my broad area of research. Finally, some places and people agreed to participate, and I spent a month in the summer of 2017 cycling back and forth to a small rehearsal space in East London, with too much equipment for one person to carry, documenting a method acting class, re-staging an ‘Standard English’ Accent class for international workers, plus setting up long shooting days with children actors, a contortionist and more to further amplify my concepts.

MA Film trailer: https://vimeo.com/244511379

The work ended up becoming a 55 minute quasi-documentary that was about the British political situation as much as it was about the construction of language, the architecture of the voice and the primitive natures of the human condition. It set up a way of working that has stuck with me for now. Most notably the freedom to integrate the ‘acted’and the ‘documented’, not just side-by-side, but completely entangled with each other. It also saw the introduction of a limitation for my videos of which I am still using now; ‘that they must be shot in one room’. This has allowed me to produce microcosms that can host disparate research materials, offering them a sense of contextual continuity; softening the potentially crude juxtapositions at play. It also allowed me to use the architecture and concepts of the stage in various sites and settings outside of recognisable performative spaces, allowing the practices of documentary, cinema and theatre to coagulate in some way or another that continues to be really exciting for me.

Post-CRA I have been extremely lucky to have a few opportunities that have kept the momentum and intensity up that you develop whilst there. In February I left for a three month residency in Leipzig to stay and work at HALLE14, Centre for Contemporary Art, as their International Artist-in-Residence. There I began work on a new video and installation around the management of subjectivity in both the GDR and contemporary capitalism through practices of Storytelling. This led to me working with the archives of a 1970’s after school children's Opera Club in Leipzig, alongside the re-staging of a Small Talk and Storytelling class for entrepreneurs, which explicitly updated Harun Farocki’s ‘The Interview’(1996) for the contemporary age, and took place on my first fully constructed set.

Furthermore, I have also been one of the recipients of the Artist Bursary Award at Jerwood Visual Arts, London, offering funding to help with specific processes in artists practice’s. Thanks to them I am undertaking my first set of fully budgeted rehearsal sessions, with two adult actors and one child actor, into a potentially new fiction film around my CRA dissertation research into Crisis Rehearsals within the work space and private spheres. And finally, right now as I write this, I am out in Italy preparing to undertake a residency in the city of Ferrara, as part of the cultural organisation Resina, whereby I am in the research phase for a potentially new video or performance.

I think it would be an understatement to say that CRA was really important to me, more so, I think it completely shaped the work I am making today, and the way I think about the world and the systems that structure it, both critically and aesthetically. It would be fair to say that what I started in CRA is still at its complete birthing point, and with each new work I seem to be learning new things about how to make, what to make and why to make. The texts shared, the conversations had, and the works explored continue to act as a point of reference to the things I do, most likely for the foreseeable future.

My name is Jacob Burns, and I completed the MA in Research Architecture in 2013-14. I had my eye on the course even when I was choosing my undergraduate degree, which was History of Art at Goldsmiths. I knew that I wanted a study path that combined politics with exciting and new theoretical approaches to some of the most important topics and environments of our time. I actually studied a year of Philosophy at Glasgow University after leaving school, and I remember being so turned off when in the first week we were told: "the most important thing to remember is that you will do nothing new here." Goldsmiths, and particularly MARA, was the opposite of that. The teaching staff always supported students in their efforts to push boundaries and think about things in original ways; celebrating unforeseen intersections between the students' work, the academy and the world outside.

What Research Architecture exactly is was always a bit of a tricky one to explain at family parties, but the way I like to think about it is this. The course teaches you about the architecture of research itself: what does it mean to build a question? What structural elements of the world do you need to be aware of to investigate pressing issues in late capitalism? That means the course throws its focus far and wide, and that can be daunting. At the end of the day, however, what I think MARA taught me was invaluable in my work after I left, allowing me to approach problems of research with an awareness of the detail and scope that is really necessary to do good work.

The course opened many doors for me. I was research assistant to Professor Eyal Weizman, the principal investigator for Forensic Architecture (FA), for two years, working with him on cases, books, essays and talks. I wrote my own essay as part of the Forensic Architecture edited volume on Sternberg. I also was a resident for three months at Decolonizing Art Architecture Residency (DAAR) in Palestine, and wrote a collaborative text with Nicola Perugini and DAAR from the research I did there.

I then worked for Amnesty International for two years, researching human rights violations in Israel-Palestine. We worked together with FA on a number of groundbreaking digital projects, like the Black Friday interactive report and the Gaza Platform cartography of the 2014 Gaza War.

Since the beginning of 2017 I decided to pursue writing full time, and have been working as a freelance journalist, reporting on politics and human rights issues from Jordan, Egypt and Israel-Palestine.

The path I've taken has perhaps not been a straight line, but I think my time at Goldsmiths was incredibly important. It gave me intellectual resources that I continue to draw on, it cultivated my curiosity in the world, and inculcated in me the confidence to get out there and get to the bottom of what I was interested in.

We are Cooking Sections a London-based duo of spatial practitioners formed by Alon Schwabe (MARA, 2013) and Daniel Fernández Pascual (PhD RA 2018). We explore systems that organise the world through food and use ingredients as a performative point of departure to critically explore postcolonial contexts, speculative imaginaries, and complex ecological networks. Our work investigates the making of the built environment and the impact that human-induced environmental transformations inflict upon humans and more-than-humans. Using site-specific installations, performance, mapping, and video, our research-based practice tests the overlapping boundaries between the visual arts, architecture, and geopolitics.

Reflecting back on our graduate experience in the Centre for Research Architecture, its important to stress that roundtable was not just a place to think and discuss ideas, but it provided us with an incredible platform to meet other colleagues and start off working together. Indeed, in our case it served as the place to run a project outside of school, following the emphasis on research-based practice that enabled us to develop new methodologies with incredible feedback throughout our time there. Besides, this unique learning process (that in many ways implied un-learning many of the things we thought we knew) helped us work towards the setting up of an independent spatial practice. It forged the foundations to operate outside academia and put critical thinking into practice.

Our work has been exhibited and circulated internationally at the U.S. Pavilion, 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale; Manifesta12, Palermo; Lafayette Anticipations, Paris; 13th Sharjah Biennial; Atlas Arts, Skye; Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin; Storefront for Art & Architecture New York; Peggy Guggenheim Collection; CA2M, Madrid; The New Institute, Rotterdam; UTS, Sydney; HKW Berlin; 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale; and Delfina Foundation London among others. In 2016 we opened The Empire Remains Shop in London and the book about the project was recently published by Columbia Books on Architecture and the City (2018). Currently we teach an Architecture Design Studio challenging the financialisation of nature at the Royal College of Art, London.

The Free Seminar began in 2015 as an ad-hoc space for student-led symposia, discussions and workshops. We met weekly with the idea of creating an environment, outside of the timetabled curriculum, to talk freely and to self-organise.

Amongst other things, we ran a cryptography workshop; learnt live-coding for music; discussed neutrinos with artist Jol Thomson; hosted a performative meal with Esther Kokmeijer and met with our counterparts at the Royal College of Art.

Irit Rogoff, a Visual Cultures Professor at Goldsmiths, gave us a class on her notion of ‘free knowledge’ (you can read her e-flux article here)

Free Seminar is a community of sorts – one that is always shifting in numbers and people. Essentially it gives us reason to spend time together and learn from each other. Participants have joined us from various programmes at Goldsmiths, including MAs from the Centre for Research Architecture and students from across the Visual Cultures and Cultural Studies BA, MA/MRes and PhD programmes.

As the meetings were at the end of the day, we arranged that each one would be a Potluck – where everyone would bring food to share with the rest of the group.

The sessions would change in format and focus, but the basic idea is: each one, teach one. We had a mixture of reading groups, film screenings and Free Seminars, where different members of the group would arrange to invite speakers, hold workshops and have discussions that overflow and augment.

In other words, we all contribute something in whatever way we want.

The Free Seminars were organised and run by the students from the 2015 and 2016 MA intakes, but as we’re all graduating this year, the group as it currently exists will cease to be. We didn’t create this idea; it exists in ever-changing forms all around the world. We’d love to see the Free Seminar continue, in whatever format makes sense for the new students, so please take the idea and turn it into something that makes sense for you.

‘The Centre for Research Architecture: A Crucial Juncture in my Bifurcated Paths of Practice.’

When I encountered the Centre for Research Architecture in 2009, my practice was in crisis. I had been producing films relating to migration and migration policies in and at the borders of Europe since several years. My first film NEM-NEE (2005), which uncovered the dire condition of illegalised asylum seekers in Switzerland, was produced as part of a wide civil society campaign to defend migrants rights. My second film, Crossroads at the Edge of Worlds (2006), attempted to produce alternative representations of transit migration at the borders of Europe, underlining migrants’ social networks and the many strategies they resort to evade state repression. But in 2007, I came across the International Organisation for Migration’s (IOM) “information campaigns”, in which they produced fictionalised representations of the conditions of precarity, exclusion and death that I had documented myself. Here, however, the aim was not to denounce the migration regime that led to these forms of violence, but to dissuade potential migrants from coming to Europe. Images of suffering had thus become tools in the government of migration, and this led me to question both the strategies and effects of my own practice. I needed to pause and ask myself: What did your films actually do? What political effects did they produce? Where they the ones you envisioned? I needed, for a time, to stop producing images of migration and enquire into the migration of images themselves.

It was during this period that I began my thesis at the Centre for Research Architecture, which provided an environment to make this crisis productive, and eventually lead out of it. I was drawn to the Centre for its unique research ethic: it brought together architects, artists, filmmakers and theorists who had in common simultaneously addressing political issues as well as the politics of their own practice. Politics then, was not something located “out there”, but rather within the practitioners own medium, working conditions and practice. The Centre was further ideal for me since it is dedicated to experimenting with blurring the boundaries between research, aesthetic practice, and political intervention. Rather than advocating distanced observation, the Centre emphasises participation with concrete actors and social realities as a form of intervention that can generate new knowledge and aesthetic practices. While critical distance is not evacuated here, it is a distance that must be created from within the intricacies and contradictions of practice – or from a position of critical proximity in Eyal Weizman’s words (Weizman 2013). In short, the aim was as much to “think what we are doing”, in the words of Hanna Arendt (1958), then to think through doing, and do through thinking. In the process, the binary categories of thought and practice are challenged.

The works developed within the Centre further had a unique emphasis on space and materiality, articulating, through case studies, the infinitely small – such as the technical characteristics of images – with the infinitely big – such as global political and economic transformations. Or more precisely, this lens allowed me to trace from within specific cases and materialities, an expansive web of philosophical questions and political conditions. Finally, the Centre was committed to collaborative research and practice: the collective and collaboratively organised seminars were a formidable processes of turning ideas around, and “individual” projects became infused with the ideas of many others. My individual trajectory has thus been deeply shaped not only my own encounter with exterior events and theories, but by the way this encounter has been mediated by a collective thought process.

During the years I spent at the CRA – I completed my thesis in 2015 – I never entirely knew where my thesis was “going”. As a practice based thesis, this probe did not seek to offer an answer to a single research question, nor is it the documentation of a single project, but rather an account of the successive stages and bifurcations in my experimentation with the possibilities of documenting and contesting the violence of the migration regime operating between Europe and Africa. If my practice-based thesis did not have either a single hypothesis that it aimed to prove or disprove, it was driven by a working hypothesis: that aesthetic practices and objects play a key role in shaping the politics of migration, either in reproducing the current migration regime or undermining it. The thesis unfolds as a “diary of practice” of sorts, in which I describe the successive shifts my research and aesthetic practice has undergone in relation to my encounter with the field of the politics of migration, as well as with new problems and potentialities that have emerged in theory and practice. The title of my thesis “liquid trajectories” refers then as much to the restive and bifurcated paths of migrants, the mobile bordering practices that seek to block or steer their course, my own trajectory of practice, and as we will see, that of the images I have produced.

The thesis retraces and reflects upon a succession of phases in my research and practice. In the first phases, which coincides with the start of my PhD in 2009 and the moment of crisis in my practice produced by the encounter with the re-appropriation of the images of migrants’ precarity by the IOM, I trace the “lives” of the images of migration I produced over 10 years, and seek to chart their variegated effects as they themselves “migrated” through different contexts and practices. In this strand of research, Image/Migration, I sought to challenge the way we conceive of the politics of the image, and shed light into the many ways in which image practices and objects have been put to use towards the government of migration or to contest it.

Looking at image practices, I attend for example to the production of Ridley Scott’s film Black Hawk Down (2001), which was shot in Rabat, Morocco, and through which illegalised sub-Saharan transit migrants hired to act as extras secured a temporary legal status as well as cash which some used to pay for their crossing to Europe. Through such examples, I show that an attention to images as practices allows us to see new and surprising ways in which image production becomes agentic in the conflictual field of the politics of migration, and that the effects of image practices may not always be those intended by their authors. Looking at the migration of images as objects, I attend to circulation of images depicting the suffering of migrants, from the hands of actors who seek to govern migration to those who contest it, and back. In Fractured Chains of Custody, I trace the stages of the circulation of a photograph of migrants’ boats set ablaze by the Moroccan military from their own documentation to my own video project Crossroads (2006) which used this image to denounce the violence perpetrated onto migrants, to an IOM newsletter concerning anti-trafficking and anti-illegal migration activities and finally its use in social media to contest the violence of borders once again. Rather than the “photographed event”, I attend to the “event of photography” in the terms of Ariella Azoulay (2008b), and to how the image operates within the successive institutional and technological assemblages it comes to be embedded in.

Looking at the role of image practices in the section Perception Management, I analyse the IOM’s media governmentality, in which images of suffering are used to deter potential migrants. In the process, I am able to address some recent shifts in the government of migration by the European Union, which no longer only seeks to control the movement of people, but also to shape the wider processes that condition migration itself – such as wars, economic development and perception. This shift entails an expansion of practices of migration management in space to encompass countries of ‘origin’ and ‘transit’, reaching a scale which is at least potentially global. In the process, non-governmental and intergovernmental actors – such as the IOM – become key partners in terms of enabling operations outside of national borders and in a wide range of fields (Kalm 2012). Crucially, these organisations adopt the language and visual repertoire of development, human rights and humanitarianism to forward the government of migration.)

A second moment of bifurcation in my research and practice (Chapter 3: Forensic Oceanography) coincides with the rupture in global geopolitics and in migratory patterns and bordering practices unleashed by the 2011 Arab uprisings, as well as with the beginning of the collaborative project Forensic Architecture initiated by the Centre for Research architecture in Autumn 2009. The project took its starting point from a recent shift in the field of human rights, from a practice based on gathering testimonies of violations to “mobilise shame” in the public sphere (Keenan 2004), to one relying on multiple forms of technical evidence – from videos to satellite imagery, the analysis of DNA to that of rubble – and geared towards the legal sphere. The collective research project was launched to simultaneously explore – through research and practice - the new possibilities that the “forensic turn” might offer, and on the other, reflect critically on its implications. This project opened a new political and theoretical horizon within which fellow researcher and architect Lorenzo Pezzani and I developed the “Forensic Oceanography” project, which sought to forge new tools to document the violations of migrants’ rights at sea and understand the conditions that shape them.

In the frame of the Forensic Oceanography project, with the assistance of technical experts and SITU Research, we seized remote sensing and mapping technologies usually used for surveillance to contest the impunity which prevails for the deaths of migrants at the EU’s maritime frontier. The cases we were able to document – in particular the “left-to-die boat” case, which led to several legal complaints against states for non-assistance – allowed to untangle the complex geography of the EU’s maritime frontier. Here, partial and overlapping jurisdictions, the patchy vision of surveillance, patterns of maritime traffic that connect the producers and consumers across the globe, mobile border patrols, and the splintering routes of illegalised migrants all converge to produce a regime of hierarchised and segmented mobility: speedy and secure for certain goods and privileged passengers, slow and deadly for the othered and dispossessed. This mobility regime is necessarily conflictual as it operates along one of the major geopolitical and geoeconomic fault lines of the postcolonial world – a division precisely contested by the unauthorised movement of illegalised migrants. The innovative methodology we developed for our investigation on the “left-to-die boat” case was the basis for WatchTheMed, an on-line mapping platform designed to enable civil society to exercise a critical “right to look” at the maritime frontier of the EU, in the aim of both documenting and preventing the violations of migrants’ rights. Here, even more crucial than the sensors of remote sensing technologies, are the eyes, bodies and networks of “citizen censors”, to use the tem forged by Michael Goodchild (2007). Together, they constitute a human-machine assemblage.

At present, while I begin a new postdoctoral project, I continue to be informed by the perspective and tools that the CRA allowed me to forge during my thesis. Within the frame of Forensic Oceanography, Lorenzo Pezzani and I have continued to forge new tools to document and contest the violence of borders, while always also seeking to reposition our selves in the ever changing aesthetic regime operating at the maritime borders of Europe. In retrospect, I can see how the CRA has allowed me to explore critically my own practice and its politics. It has allowed me to attend to the materiality and technologies involved in the aesthetic practices and objects I have attended to and produced, as well as to be attuned to deep global transformations. It has pushed me to engage with migrants and migrants’ rights organisations as part of my research, and thereby allowed me to simultaneously contribute to (modestly) transforming and understanding the world. By engaging with aesthetic practice and non-governmental politics, I have been able to shed new light on the ongoing transformations of the politics of migration, themselves a dimension of the shifting political geographies of our postcolonial world. I would strongly encourage curious, committed and daring students to embark on what has been for me a deeply transformative learning experience.

Read more about the Forensic Oceanography project on Forensic Architecture

(This text is an edited excerpt of the introduction to Charles Heller’s PhD thesis “Liquid Trajectories: Documenting Illegalised Migration and the Violence of Borders.”)

My name is Hania Halabi, a graduate of the Research Architecture MA 2014-2015. I completed my BSc in Architectural Engineering at Birzeit University in the West Bank. In my third year, I attended an experimental design studio that looks into architecture beyond its conventional definition as the process of planning, designing and constructing buildings; transforming it into a medium for political criticism and change. The assigned project on “re-imagining the Palestinian Parliament” was inspired by the work of Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency (DAAR), and exposed me for the first time to different aspects of the intersection between architecture, conflict and power. My interest in the field continued to grow from there.

After graduating from Birzeit University I started working at Senan Abdelqader Architects while looking for relevant Masters degrees abroad. Senan invited Eyal Weizman to join the jury of a competition I was working on for the company, and it was this that led me to apply for the Research Architecture MA. I should also say that I couldn’t have considered the programme if it weren’t for Goldsmiths’ humanitarian scholarship, which I was awarded in 2014. As part of the scholarship scheme, I also finished a leadership course where I was assigned to be a student ambassador.

My year at the CRA was one of pure exploration, which has advanced my understanding of the world I engage with on so many levels; it was a journey into my own interests (which I lost and found several times throughout the year). The program is flexible rather than specific in many ways, but it teaches you how to plan a methodology, design a narrative, and construct an argument that responds to the most urgent and critical topics of our time. Architecture becomes a conceptual medium to approach, navigate and investigate the topic at hand. For my own thesis, I looked into the conflict of the Palestinian village Susya located in Area C, and unpacked the secrecy and agency of its architecture by analyzing the politics of its materiality.

During my time at CRA I had many opportunities to engage outside of the course itself, all of which have fed into my experience and understanding of the research process. Firstly, I helped with the Forensic Archiecture Black Friday on Gaza, which also led to further collaboration after my graduation. Secondly, I joined a research group called “Open Gaza” based at Westminster University to pursue individual research that inquires into the relationship between architecture, time and emotions - I later presented this research in a conference at Max Planck institute in Berlin. Finally, my enthusiasm towards exploring fabrication experiments and algorithmic design drove me to complete the Architectural Association’s MakeLab programme in April 2015.

After my graduation from Goldsmiths I decided to apply for research jobs in London, and against all odds I was offered a research position at Balmond Studio, leading the personal research of Cecil Balmond OBE on ‘form making in abstract environments’ towards publication. Though the topic was so different from anything I did at Goldsmiths, I learned that it is the process and lens through which I approach the research that matters. At Balmond Studio I led a think tank called “CrossOver” for eight months, and most recently started new research on emergence theory in urbanism and finding new ways of re-imagining the slums worldwide: research I would like to pursue in the future individually, in the context of Palestinian refugee camps.

Despite the degree being research-based and having theoretical focus, it didn’t limit my chances to take lead roles in other areas. The CRA helped me to cultivate a mindset that I didn’t know I had until I began to face various challenges at work, and I realised that the key to solving them was critical thinking. I am now working in architectural design, which I love, and I feel so privileged to be able to consider my work differently, and more critically. I still feel I am navigating my way along my career path, but I surely wouldn’t have been where I am today without my time in CRA.

My name is Grace Phillips. I completed the MA in Research Architecture in 2015.

My name is Grace Phillips. I completed the MA in Research Architecture in 2015.

While researching for my undergraduate thesis (BA Earth Systems Science, BA Philosophy), I used data compiled by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. It was through their collaboration with Forensic Architecture that I discovered the Centre for Research Architecture. After completing my degree, my advisor joked that he found a great book I should have read a lot earlier. It was Least of All Possible Evils by Eyal Weizman.

So I applied for the MA. At Goldsmiths I ran in circles before eventually settling on something relatively familiar. My dissertation was on meteorology and epistemology, specifically the challenges of taking an invisible material (the air) as an object of science. The implications of an observation practice that occurs when the object of study is vast and only visible as it appears in other things (i.e., wind) raised important questions for me about vantage points and how relations might be understood to be as real as objects.

CRA provides a lot of space; it is possible to remain quite suggestive and, due to the brevity of the MA, unresolved. This was both unsettling and surprisingly productive when it came to formulating and applying ideas. The other key element of the program for me was the people in the MA. The process of translating myself to a small cohort gathered only by a loosely sketched notion of architecture created completely new possibilities. Actually translating the whole thing to anyone was a strength-building exercise.

Vantage points is sort of what I ran with post-CRA. I currently work as a writer and freelance journalist. I’ve been able to independently report from major events, like COP21 in Paris (2015) and Standing Rock (2016). I spent winter 2016-17 in the Bakken oil fields in eastern Montana/North Dakota, living, researching, and writing. In September I returned to Montana after a residency in Finland. Forthcoming work is on relations, drawing distinctly, if indirectly, on ideas pulled together during my time in CRA.

I’m Solveig Suess, and I graduated from the Centre for Research Architecture’s Masters programme in 2017. Like a few of my classmates, I had come from a background in Visual Communications and have been practicing as a freelance Graphic Designer since several years. Like many, I was eager to find a more meaningful practice, expanding out from and beyond the skills I already had. What had brought me to apply to the program was how practice and aesthetics are placed equally alongside academic rigor and meaningful activism- with the idea that I would be amongst others that were also eager to situate their work within broader discussions and movements.

I’m Solveig Suess, and I graduated from the Centre for Research Architecture’s Masters programme in 2017. Like a few of my classmates, I had come from a background in Visual Communications and have been practicing as a freelance Graphic Designer since several years. Like many, I was eager to find a more meaningful practice, expanding out from and beyond the skills I already had. What had brought me to apply to the program was how practice and aesthetics are placed equally alongside academic rigor and meaningful activism- with the idea that I would be amongst others that were also eager to situate their work within broader discussions and movements.

During our first week of classes with Irit Rogoff, I remember her poignant way of addressing our joint anxieties when faced with the endlessly complex challenges of ‘globalisation’. Where do we even begin? How can we find entry points into such projects of totality? How can we start to understand when its scales exceed our imagination? Many long classes were spent sometimes excruciatingly pulling apart things we had grown up ‘to know’, followed by a slow processes of threading these pieces back together into other constellations. Our core classes which included Conflicts and Negotiations across Spatial Practices with Susan Schuppli paired with the Introduction to Research Architecture with Louis Moreno and Studio with John Palmesino, each acted foundational to the discourses and aesthetic strategies I build with today. This course may not give you a clear direction to go in, but it lays down a series of coordinates which acts as guidance.

Aside from the structure of lectures and support from our main tutors, much of the course as an experience depended on each of our own efforts to devote time into group studies and projects. My classmates and I were very willing to contribute and organise amongst ourselves where events— such as the student-led Free Seminar where guests were invited for workshops and lectures, or the projects made during our class residency at the Arts Catalyst Centre— these events had brought us to experiment ideas together as a class. Collectively, we learned to discuss our diverse interests and to struggle with one another across disciplines, class, backgrounds, situations- which, to be honest, were rarely smooth experiences but felt meaningful nevertheless.

There was a lot of generosity that can be felt from tutors and students across the Visual Cultures department, especially when it came to collaboration. Louis Moreno and Irit Rogoff (freethought) had involved a few of us classmates Sophie Dyer, Robert Preusse, Laurie Robins and myself in their collective’s project for Bergen Assembly while Sophie Dyer and I had designed for Forensic Architecture’s exhibitions that same year. It was inspiring to see the processes of our own tutors in how their own practice and politics are mobilised, but also to be in discussion with them while developing and being involved with our own. During the political tidal waves from Brexit, the slow privatization of our universities, losing our tutor Mark Fisher— there was a surge in activities organized by various student bodies and tutors across the department, and their inclusive energy felt particularly important during such times where we experience these events at once similarly, and otherwise so differently.

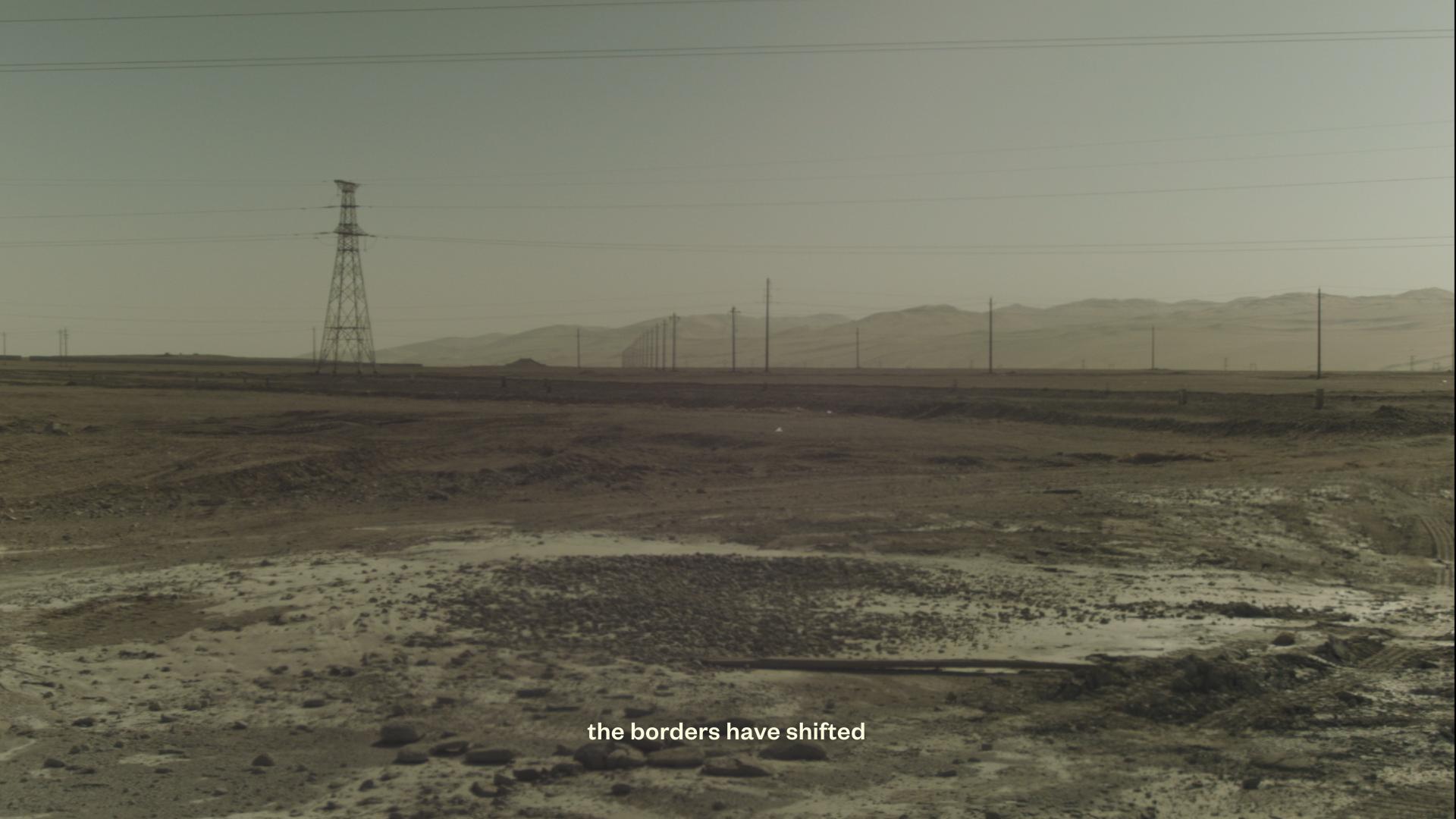

My time at the Centre had nurtured a commitment towards a documentary practice which coincides a longterm research interest into infrastructures of migration, trade and optics across geographies affected by increasingly strange weathers. I had chosen to focus on the Chinese-led infrastructural project of the New Silk Road for my dissertation and project, where as slowing economies increasingly depend on the use of logistical innovations to reconfigure geographies of supply and demand, there is an urgency to understand these studies alongside both weather management and of biopolitical methods of containment. Here, fundamental differences made at levels such as inventory lists, scale up to matter in very physical, cartographic, temporal and cognitive ways— further perpetuating formations and expansions of extractive frontiers. To me, documentary felt important as an embodied method in mapping out these relations.

During the final stretch with dissertation writing, Susan Schuppli was my main supervisor. She had been endlessly generous with her guidance throughout times of personal struggles with writing and my still unformed filmmaking process. It was guidance like hers which gave me a lot more confidence in pursuing the directions that I have. I ended up making my first documentary for the final degree show and was fortunate enough for the piece to continue circulating after the show came down, including for it being selected to screen at the 2018 Rotterdam Film Festival. The film had woven together a series of encounters, footages, interviews, field recordings, found WeChat videos and collaborations; such as with parts of the script written by friend and classmate, Ming Lin.

Soon after the masters, I continued into an artist residency with Sophie Dyer at Tabakalera Centre for Contemporary Arts where we further developed 流泥 Concrete Flux; an experimental documentary platform that publishes accounts of aesthetic journalism. I later pursued a postgraduate course in the 2018 New Normal program at Strelka Institute, which led to the research and film led inquiry I’m currently working on called ‘Geocinema’. Under the Digital Earth fellowship, I was granted time and space to pursue certain research strands in China which traces the twinned histories of Chinese satellite technology and changing meanings of the lands it records. Two years on, I’m plotting my next documentary while working with a cooperative designing and developing open source software for climate change adaptation and environmental engagement, called User Group. The current direction of work that I’ve developed really stemmed from my time spent at the Centre and I’m incredibly grateful for the support I continue to feel from the department.

I am a Centre for Research Architecture alumni from 2017.

I am a Centre for Research Architecture alumni from 2017.

Before spending the year at Goldsmiths I worked as a photojournalist in Israel/Palestine for many years, documenting news stories and social struggles. In 2005, I co-founded Activestills, a collective which uses photography as a tool for social and political change. We document a wide range of different struggles and human rights issues in the region, working on the premise that our photos are also owned by the communities we work with. We focused on distinctive ways to exhibit our photos (such as street exhibitions and online), so that as many people as possible would be exposed to the events taking place in Israel/Palestine. Our photos were used for legal purposes, fundraising and protests. I have personally collaborated with most of the human rights and activist groups working in the region.

I chose the Centre for Research Architecture because I wanted to further expand my work with visual materials. I also felt that the programme would also allow me to develop my writing and research skills. What I particularly liked about the programme is the diversity of subjects the students came from: there were artists, journalists, architects, intellectuals, and others. These different specialisations made for a really interesting and inspiring group. I also valued the practical aspects of the course; both the Forensic Architecture internship and other applied workshops taught me new skills and approaches I hadn’t worked with before.

During my internship at Forensic Architecture I learnt how to combine my existing skills with FA’s approach to investigation. We worked on a project in real time, as well as on an exhibition piece.

For the Exhibition I worked with my photographic archive from the village of Al Araqib, which was created as part of my work with the Activestills collective. Together with Ariel Caine and Eyal Weizman, we edited my photos from Al Araqib, from before the first demolition in 2010 up until 2017. The photos show the daily life in the village, its demotions, the police raids and arrests, as well the daily struggle of the residents to remain on their lands which continues up to this day.

During the editing process, we felt there were a lot of materials missing. As an outside photographer, it is hard to document every demolition and other important moments in the village. We contacted Aziz, a prominent activist in the village, and other residents, who allowed me access to their private cell phone photo archive. We edited their photos together with the Activestills ones, and created a grid of over 400 images, from 2009 until 2017. The grid is composed chronologcly, while as the same time also features specific themes and short photo essays.

The piece was also exhibited in the MACBA museum, in Barcelona in April 2017. The Negev exhibition, then travelled to the Biennale in Beirut and later to Vienna, as well as to Tel Aviv. The photo grid we edited was also presented at an event marking seven years to the first demolition of the village, which took place in the village itself. The grid was printed on a big plastic roll which can be folded and hidden from the police, during future raids on the village. For me this event was another landmark in Activestills engagement in Al Araqib’s struggle: seven years ago, we printed the first exhibition hung in the village, and since then our photos were used in vigils and protests, and used to advocate during various solidarity visits to the village. The images were also used in the 3D map created by Ariel Caine, on which the photos are geo-tagged and viewed interactively.

The Umm al Hiran investigation had several phases.It addressed an incident which took place on the morning of January 18, 2017 when Israeli police raided the Bedouin village of Umm al Hiran, and demolished a few houses. This demolition was part of a plan to remove the unrecognized village, to make way for the Jewish village of Hiran. As police forces advanced in the dark towards the village’s houses, the police shot and killed Yaqub Abu al Qian. During the incident, officer Erez Levi was killed and another policeman was badly injured. The police claimed that Abu al Qian was affiliated with ISIS and was trying to commit terrorist attack using his vehicle.In the Israel media, the story was immediately presented as a terror attack, claiming that the Bedouin man was trying to kill policemen. The situation was still unclear, and media were prevented from entering the village.

The First Phase took place while the event was still happening, I received a raw video from Activestills photographer Keren Manor, who was one of the only two journalists present at the scene from the early hours of the morning. The short videos captured the shooting and the events following it, but it was dark and unclear. The raw video itself was published on social media and taken by mainstream media as it was the only documenting from the shooting.

Together with Eyal Weizmanand the team in the FA offices, we started to work on the story, while the event was still unfolding. Meanwhile other witness (such as activist Kobi Snitz), sent their testimony and a few other photos.

We watched again and again the raw video trying to locate car numbers and locations, using a satellite imagery released by police and other images. Speaking to people on the ground it was clear the police story was false, but we needed proof. By noon time, the Israeli police published a voiceless aerial video of what they claimed was the ramming incident. In some of the versions, the police added marks and subtitles to narrate the events.

We took the police video, and linked it with Keren’s video from the ground, by using the flares of the police gun shots. Connecting the two elements, the police video and Manor’s audio material w created a sound track for the aerial police video- which showed that, Abu al Qian was shot before hitting the policeman. We claim, that only after he was shot, his car escalated and hit the policeman. After 40 hours work, two days after the incident, we published our report on the alternative media platform +972 Magazine and Local Call. On social media, many bloggers and activists, including Haaretz blogger ‘John Brown’ and MK Ayman Odeh, shared our report. In reaction Israeli police claimed that the video was falsely “edited”.

The Second Phase Report was published two weeks after, we confronted with one of the main claims of the police, which was that Abu al Qian was driving with the car’s headlights off.

After going through all the videos we could find from the scene, we located al Qian’s car in an Al Jazeera report from the same day. Footage of the car was used as backroad video from the reporter’s comment. Even Al Jazeera did notice it. The fact we have been working on the case for weeks, allowed us to insure it was Al Qian’s car. The video showed it had the lights on. We could have just tweeted it, but worked for another full report, showing the methods used to insure it was the right car. The report was published in Haaretz, +972 magazine, and later also on the Israeli Channel 2 TV, Walla!, Ynet, Al Jazeera, The Jerusalem Post and more.

In this case, the report had a major effect on the public discourse in Israel, and even on the police internal investigations department. Following, the Internal Security Minister Gilad Ardan, had to change his initial statement, and withdraw his claim that Abu al Qian’ was a “terrorist”.

Video contradicts police claims

The Third Phase was a summary of all information gathered. It included also new findings, discovered during the civil reenactment done by the FA team, together with Eyal Wtizman, Ariel Ken and Princeton students from the Architecture department, held as part of a field trip to Israel and Palestine on March 2017.

During the reenactment, we interviewed people who witnessed the events on the scene: MK Ayman Odeh (who was shot and injured that day), Israeli activist Kobi Snitz (whos testimony was the first to oppose police claims), and Umm al-Hiran resident, Raad Abu al Qian. In contrast to a testimony given in court, this collective work was supposed to expose new evidences around the event, by adding different layers of information. Firstly, we interviewed Odeh, Snitz and Raad one after the other. Later, we created one-on-one reenactments of the car’s path, from the moment Abu al Qian started his car in his house parking lot, up to the moment when the car was stopped. We used the same car model, and actors stationed as policemen on the ground. .

The reenactment was filmed from inside and outside the car, following which we learned two important things: 1) The police opened fire only 20-30 meters from the house, when Abu al Qian was just leaving his parking 2) By using the same model of car, we learned that in this specific model, the doors are locked when the cars speeds over 20km per hour. From the video and other evidences, we understood the door was open, after the car stopped. This means that Abu al Qian was injured, but managed to open the car’s door - despite the fact it was parked on a sloop. This matched a leak of the after official death exhortation, which states that Abu al Qian was left to die, and died from losing blood only after 20 minutes.

My MA Disseration examined the growing phenomenon of individuals arrested in Israel/Palestine for their social media activity. I argued that while Israel justifies these arrests as a part of its cyber security strategy, they are in fact the continuity of old policing methods, now operating through new mediums. Since the Autumn of 2015, Israel has jailed approximately 400 Palestinians for social media activity. Israeli politicians have argued that as well as being a platform where Palestinians can express resistance, Facebookis also the driver of the most recent and ongoing wave of stabbing attacks in Palestine/Israel. In my thesis, I showed how Facebookbecomes the perfect mechanism through which every Palestinian can come to be conceived of as ‘terrorist’. Through different means such as data mining, profiling and translation, the potential exists to transform any banal Facebookpost into a crime. I was interested in the way humans and machines “read” Facebook posts turning them simultaneously into evidence and the crime itself. The translation of Facebookposts (from Arabic to Hebrew)turned out to be central to this process, as was mobilizing the notion of incitementas it is defined within criminal law. As a parallel focus, my thesis also offered a way to re-think how dissent can operate in a place in which any social media activity can come to be seen as a crime.

The input of the tutors, inspired the development of a more conceptual approach to the news stories and archival work I’d been conducting before.