Photography in the Solomon Islands

Gathered in the smoke-filled shade of a large communal cooking hut, the villagers of Bulelavata pass around a photograph of two Roviana teenagers.

Primary page content

The photograph, or perhaps photo-object is a better term here, incites a whole range of responses. Old men talk sadly about the kastom (‘tradition’) that might be reclaimed through the photo-object – the large wooden earrings, clothing, lime-stained hair, and face decoration mark the image as one from “before”. The ‘crack’ is taken as a sign that the photo-object itself – not the glass-plate negative from which it was reproduced - was damaged in an attack on Roviana carried out by the Royal Navy in the late nineteenth century. My discussion of the glass negative is met with indifference. People speculate that the descendents of the two teenagers can be recognised by comparing their faces to those of the living. Fathers complain about their own teenage sons, who hang listlessly about the village avoiding the subsistence work of gardening and fishing. These teenagers, whose cheap sunglasses, knotted red bandanas, and over-sized clothes show the influence of Ragga music and also raskol styles from Papua New Guinea, laugh dismissively at the photograph. But later, out of parental view, they express more curiosity. Women laughingly point out that teenagers are still obsessed with how they look and, talking about the ruf boys of the village, they make a series of thinly disguised sexual innuendos.

The archival photo-object is re-animated through connection to these kinds of living contexts, revealing photography’s connection to a plurality of histories. The book considers the kinds of ‘savage’ images of Roviana people that were constructed through photographs taken by colonial officials and missionaries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. But in doing so, it remains aware of the kinds of images of themselves that Roviana people actively sought to promote. Throughout much of the late nineteenth century Roviana people were able to dictate the terms of trade with Europeans – so much so that Europeans were forced to manufacture copies of local shell valuables out of porcelain as an acceptable form of currency. At this historical juncture there may have been a certain utility in Roviana people promoting an image of themselves as ‘savage’, and photographs need to be considered as the outcome of a complex series of negotiations rather than taken simplistically as the imposition of a ‘colonial scrutiny’.

During my fieldwork in the Solomon Islands I was particularly concerned with some of the issues raised by W.J.T.Mitchell when he asks “what do pictures want?” How do images have ‘lives’, what kinds of agency do they possess, and is this always only possible as a mirror of human subjectivity, or, as Bruno Latour has suggested are there other forms of object/subject relations that must be accounted for. The particular images I am concerned with here are photographs, and the sense in which there is a 'magic' of photography that is all too often disavowed in certain anthropological contexts.

At the end of Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes makes a complaint – “Society is concerned to tame the photograph, to temper the madness which keeps threatening to explode in the face of whoever looks at it”.

This is witnessed by the many acts of defacement, alteration, cropping, fingering, scraping, destruction, preservation etc. that are regularly performed on photographs (I am talking here of photographs that are the result of light falling on a sensitive emulsion). These acts only serve to underscore the lives that such images have, the ways in which they impinge on our lives, their addictive qualities.

My research attempts to explore this incendiary and animating potential through looking at some aspects of photography in an area of the western Solomon Islands called Roviana, and attempt to delineate certain points of contact between Euro-American photographic practices and Roviana ones – keeping each in tension with the other. In doing so I recognise the illusionary nature of considering photography as a unitary whole, and want to argue that what is required in its place are ethnographic accounts of photographies (plural), before any easy assumptions can be made as to the identity of photography and its actions upon us.

In his 1955 account of missionary life in Roviana, Luxton noted a particular local post-mortem practice;

“when a child died it was placed in an elevated position near its parents house and a length of bush vine connected the corpse to the house to prevent it being lonely.”

This seems to provide a willing analogy for photography. As Jacques Derrida points out;

“when Barthes grants such importance to touch in the photographic experience, it is insofar as the very thing one is deprived of, as much as spectrality as in the gaze which looks at images…is indeed tactile sensitivity.”

To what extent are expectations and uses of photography a product of cultural contexts, or inherent in the medium? These are problematic but productive issues for understanding photography within cross-cultural encounters. Judith Binney and Gillian Chaplin’s project to take early photographs back to Maori communities is strikingly similar to the situation I encountered in Roviana;

“Bringing the photographs was as if we were bringing the ancestors, the tipuna, to visit. Some of the oldest people talked directly to the photos…Our visits [similarly] became a reunion between the living and the dead.”

Binney and Chaplin report that for many Maori people photographs can possess mauri, life force, and this is also the case in Roviana in relation to ideas about souls and shadows.

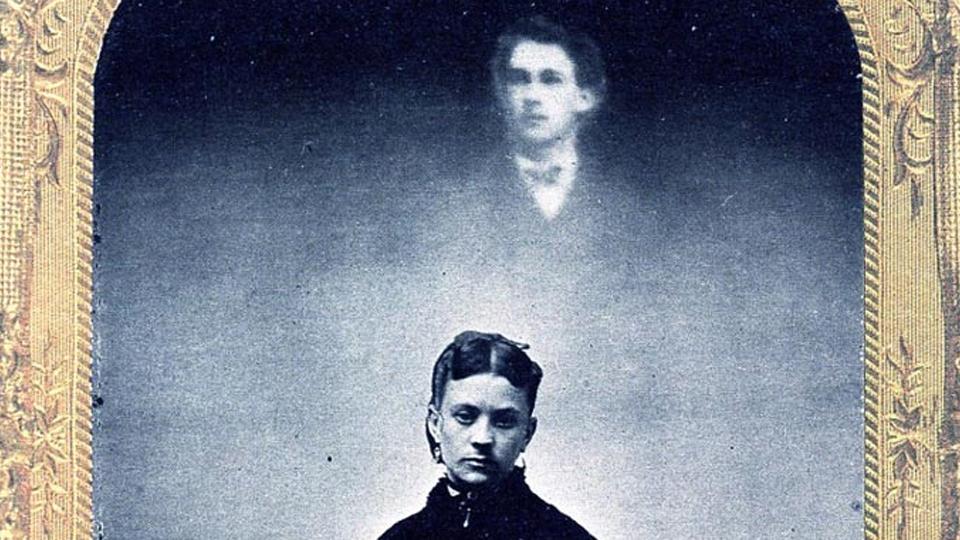

Geoffrey Batchen has argued that early photographic practices in Europe and North America are in some respects a development of the tradition of preserving actual bodily relics, like the lock of hair. Many early cases for daguerreotypes also contained a space for hair - “a talismanic piece of the body thus adds a sort of sympathetic magic to the photograph, insurance against separation”. Some cases for daguerreotypes were designed to be worn as jewellery, again reinforcing a sense of physical connection. From their inception photographs have had a physical connection to the person depicted. This is the ‘primitive’ practice whose traces haunt contemporary Euro-American photographic practices, and, as Batchen and Elizabeth Edwards have suggested perhaps “photo-objects” is a better term than photography.

In 1843 Elizabeth Barrett wrote about daguerreotypes;

“the Mesmeric disembodiment of spirits strikes one as a degree less marvellous. And several of these wonderful portraits, like engravings - only exquisite and delicate beyond the work of graver - have I seen lately longing to have such a memorial of every Being dear to me in the world. It is not merely the likeness which is precious in such cases - but the association, and the sense of nearness involved in the thing, the fact of the very shadow of the person lying there fixed for ever. It is the very sanctification of portraits I think.”

Daguerreotypists advertised their services with the slogan "seize the shadow ere the substance fade", and the images were endowed with a supernatural force that animated them. People were scared of having their image 'taken'. They were 'living pictures', and "in sentimental and celebratory verse they are indeed living spirits, animated shadows, or souls of the dead." In relation to daguerreotypes, Alan Trachtenberg has talked of the "long-repressed belief and feeling that likenesses - shadows as well as reflections in mirror surfaces - are detached portions of living creatures, their soul or spirit". In this respect Euro-American photography comes to resemble Roviana headhunting.

The Roviana word most commonly used to describe the soul is maqomaqo, and this is also the word used for a photograph. A photograph is amaqomaqo, and the term is a ubiquitous feature of contemporary descriptions of photography and photographs. Variously glossed as shadow, shade, reflection, spirit, or soul, maqomaqo is used to refer to the photograph as an object, and also figures prominently in descriptions of photography as a process. The anthropologist Lucien Levy-Bruhl argued in the 1920’s that - "very often…the vital principle or 'life' of the individual is not to be distinguished from his shadow, similitude, or reflection…'soul', 'shadow'”, while also pointing out that “these are words fraught with ambiguity, inexhaustible sources of error".

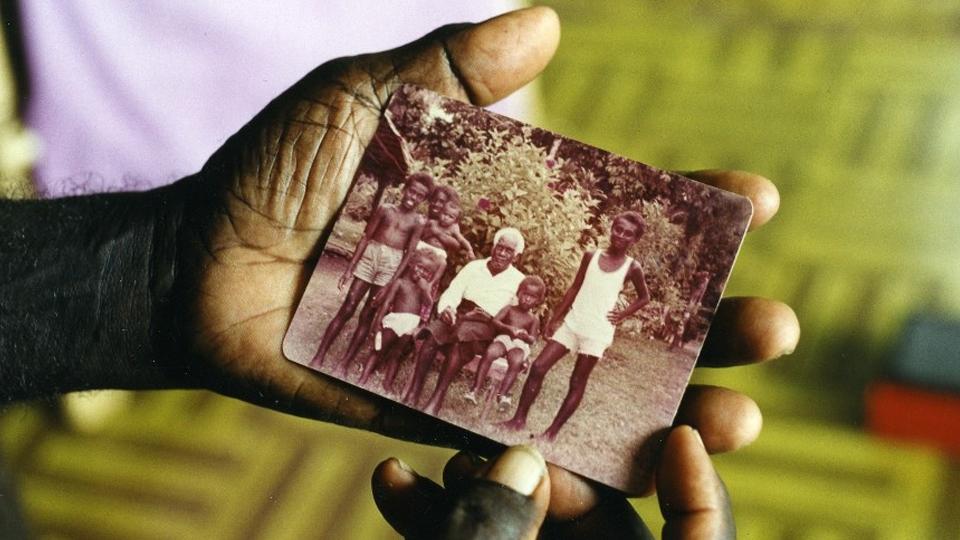

Roviana people told me how their ancestors had put mirrors, acquired from trade with Europeans, on shrines. They also repeated stories of souls being caught in mirrors - the adoption of European media into local schemes of transubstantiation. In 2001 Makoni described his encounter with his photograph of his father in the following way;

"When I saw it he was alive. I kept that photograph (maqomaqo) and after he had died I looked at that photograph again and I thought that my father was still alive. When I look at that photograph I say 'that is my father'. Photography is the shadow (maqomaqo) on the paper (pepa). They caught the shadow. When I look at the photograph (maqomaqo) of my father his spirit (maqomaqo) comes to me, he looks at me. When I talk to the maqomaqo he sees me, and hears me too."

The reciprocity of vision referred to here is an important feature of the use of photographs in Roviana - to be in the presence of the photograph is to be seen by the spirit of the dead ancestor and to be able to communicate with them. This communicative efficacy is a key element in attitudes towards a range of material relics related to ancestors - including shell valuables and photographs - and is an important component of contemporary Roviana attitudes towards ancestors and spirits.

In Roviana souls, spirits, shadows, ghosts and photographs are all subsumed under the term maqomaqo, and it is maqomaqo which animatesphotographs, that gives them life, as it does certain other relics and forms of material culture. It is maqomaqo that guarantees the efficacy and power of these objects.

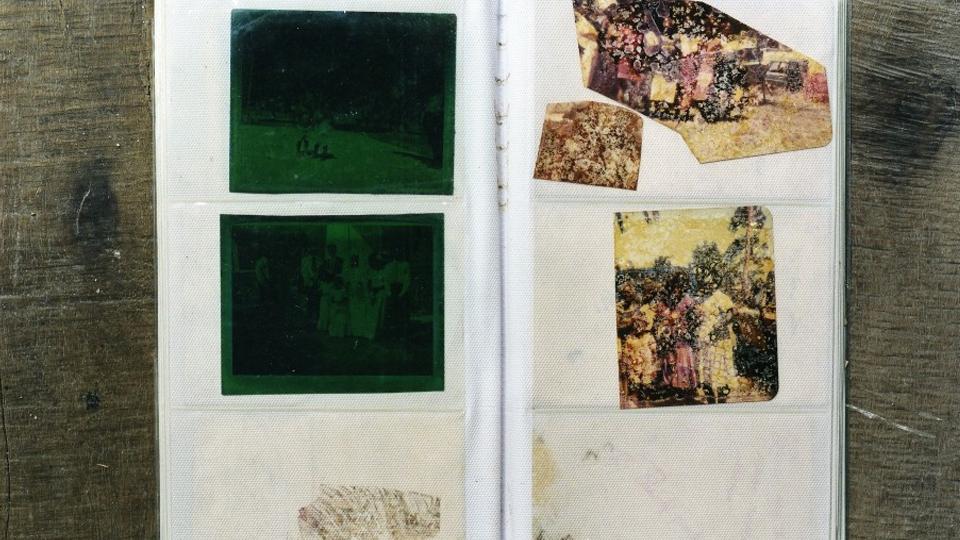

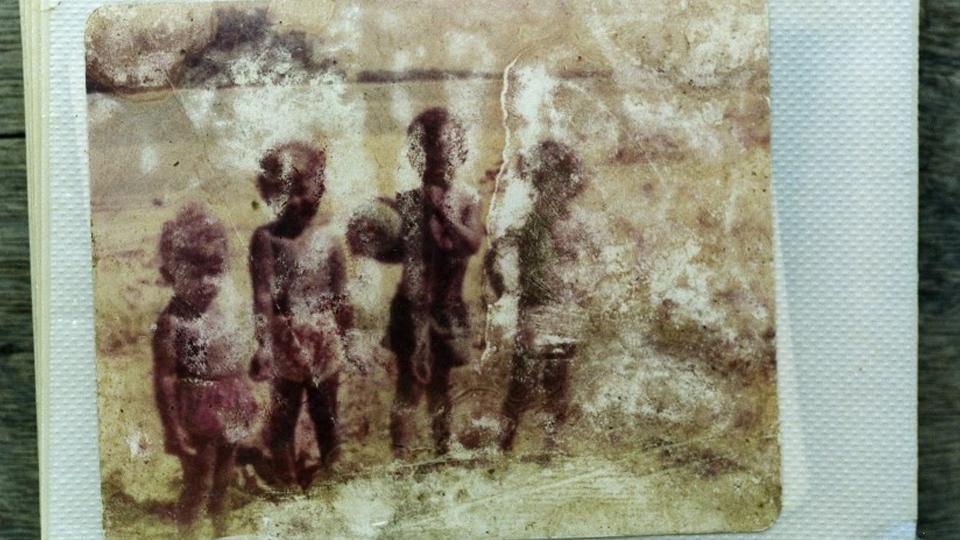

The heat and humidity of Roviana means that contemporary colour prints of the Snappy Snaps type (usually made in Australia) completely decay and disappear after a year or so, the colours runnings and blurring until the image is no longer recognisable. This decay and the material flux that it implies is the cause of much anxiety for Roviana people;

“I am not clear in this. I do not come out good. If I do not come out clear then I can get sick. There is a spirit (maqomaqo) that looks at you. This is called pela [a kind of Roviana ‘evil eye’]. The evil spirit (debildebil) can eat you.”

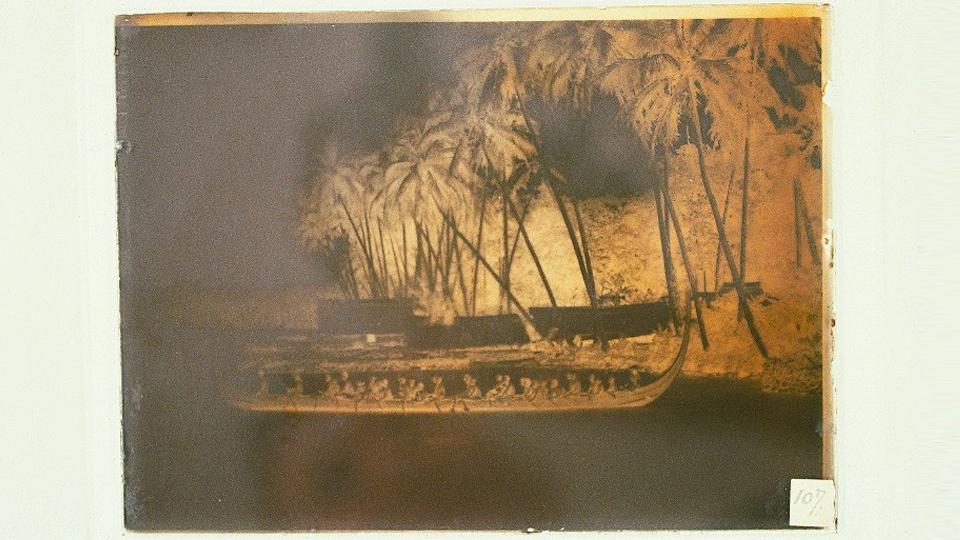

The disruption of identity that is figured in the photograph concerns a kind of visual ingestion. Roviana beliefs specified that kita - a type of slow wasting disease that reduced the body - was thought to be the work of ghosts. The disappearance of photographs is similarly thought to be the work of malevolent spirits. The concern over the disappearance of photographs and the way in which wholly illegible images like this (slide) were described to me as “this is Robertson on the beach”, demonstrates the mimetic power of these photo-objects in contemporary Roviana. But the rapid degradation of photographic prints turns the living into ghosts, and the decay of the soul that is pre-figured in these photographs threatens the sense of continuing connection to the self and to ancestors that photographs can provide in Roviana. As Chris complains; “what will I leave behind? I will not remain (stap). How will those that come after remember me?” The ‘comforting solidity’ of photographs, one of the features that underwrites their memorial function, is replaced here by the fear of being forgotten.

The decay of contemporary photographs is also seen as symbolic of the current state of affairs in Roviana and in the Solomons as a whole. The fact that some black and white photographic prints – those made between 1930 and 1960 - remain "clear" in contrast to colour prints of more recent origin is seen by older Roviana people as a vindication of how things were better "before". Now;

“Things are bad. No-one listens to kastom. People before were strong and they listened to kastom. Now things are broken (bagarap).”

The civil unrest in the Solomon Islands was a significant feature of life during the period of my fieldwork, and heightened uncertainties about the present and the future. This was brought into further relief by the copy prints of nineteenth and early twentieth century photographs that I had brought with me. Roviana people were amazed that objects that were so old could be so “clear” and my efforts to explain that they were copies were mostly ignored.

Among the range of images displayed on one wall in Chris Mamupio's house is a framed photograph of his father, Simon Mamupio. The wall is a display site that confronts anyone visiting Chris; its striking colour and the images make it the focal point of the room. For Chris this is an image which is especially "strong" and, when he talks about it he does so in the reverential tone which is a feature of stories about ancestors. The “maqomaqo”, as Chris calls it, was taken in 1974 by an official from New Zealand when Simon was inaugurated as a chief. His pierced and elongated earlobes, are visual markers of Simon's connections with "the time before" (he was one of the last generation of Roviana men to have their ears pierced). Chris made the photograph's wooden frame himself after his father died in order to "keep him safe". Simon died in 1991 and "after that there was no respect anymore". Chris told me why the photograph was so important.

"Some people worry about the spirit in the photograph (debil long pikisa), but I get power from it. I get blessing (tinamanai) from my father when I look at the photograph…It makes me dream (putagita) about him. I talk to the photograph, that is why I put it on the wall. I sit with him. My daughter has a copy of the photograph that she speaks with. The photograph can give a gift, it has power. People can see him."

Chris talks to his father at his Christian grave, and talking to his photograph, which he does daily, is an equivalent process; both allow him access to ancestral sanction. Chris's performance of the photograph includes showing me his drawing of a stepped genealogical 'pyramid', with earlier generations forming the base and himself at the apex. Chris has fourteen photographs and, apart from one of him and his father which was taken by his daughter Sarah, all of them were taken by outsiders, with the exception of one or two by other Roviana people. When he first saw a photograph in the 1930s, Chris called it a maqomaqo, and this is also how he refers to the religious prints on his wall, acquired through his daughter who works in Honiara. For Chris the image of Christ and the photograph of his father both conjure up a presence.

"The camera (kamera) takes something, something inside a person. When someone dies their soul (maqomaqo) leaves them. You can see it. People before thought that the camera would take something out of your body and you would become weak and sick. The spirit (debil) at a shrine could take your soul if you let your shadow fall on the shrine. People thought that the camera and the radio were dangerous things and they were frightened of them when they first saw them. But I think photographs are strong. With this photograph (maqomaqo) I can remember my father. When I look at the photograph my father sees me. I ask him questions and he answers.”

Chris Mamupio's photograph of his father provides him with access to ancestral sanction and power, and in the sense that it embodies his fathers spirit, it is a relic that fulfils some of the same roles as ancestral skulls. But, although they may be of great importance in connecting individuals to ancestors, photographs possess little of the public political sanction that was inherent in the veneration of monuments such as skull shrines. One of the motivations for Chris's display of the photograph of his father is so that "people can see him". The image acts as evidence of Chris's genealogy. Even though photographs are addressed as ancestors and maintain a connection for individuals, they have no connection to places. The topography that is mapped by photographs in Roviana is social, not geographic as is the case with shrines. Individuals get blessing from photographs of their ancestors, and photographs make ancestors present, but they are not public symbols in the sense that shrines were and, to an extent, still are.

Large flakes of snow fall to the ground that has already been blanketed by a thin white layer. Their slow erratic movement has been suspended by the camera, yet it is seductively easy to visualize the snow continue to fall. It is also easy to describe this “paltry paper sign” as if it were the event rather than its mediation. The photograph was taken by Clarinda, a teenager from Ilangana (a hamlet of Munda, Roviana), when she was a scholarship student studying medicine in New Zealand in 2000. That night in Christchurch was the first time she had experienced snow and her mother, Voli, tells me that she took the photograph because she wanted to share her excitement with her parents and family back home. Voli shows me handwritten letters from Clarinda in which she describes the photographs she sends back as a way of “keeping in touch”. The physical connotations are important. Before she left, her father, Isaac, had brought her a cheap 35mm Japanese automatic camera from a Chinese store in Honiara with just that purpose in mind. Other photographs in the album sent home by Clarinda show moments recorded by her friends – sitting with a boyfriend playing computer games at a console in a Christchurch arcade, with her stuffed toys in her university dormitory room, in a café with friends...

Sitting with Voli on the floor of her house close to the lagoon’s edge passing these photographs back and forth to each other, asking questions, and telling stories. There seems to be something immediately recognisable and reassuring about these objects and this process. Laughing about snow while sweating in the intense heat and humidity of early afternoon that has sent people searching for shade in which to sit and talk. The kinds of ‘contact’ that are facilitated by these photographs, “maqomaqo” (shadow or soul) as Voli calls them, are clearly of great value to her. They are rituals of family - a way of being connected. They provoke laughter and tears.

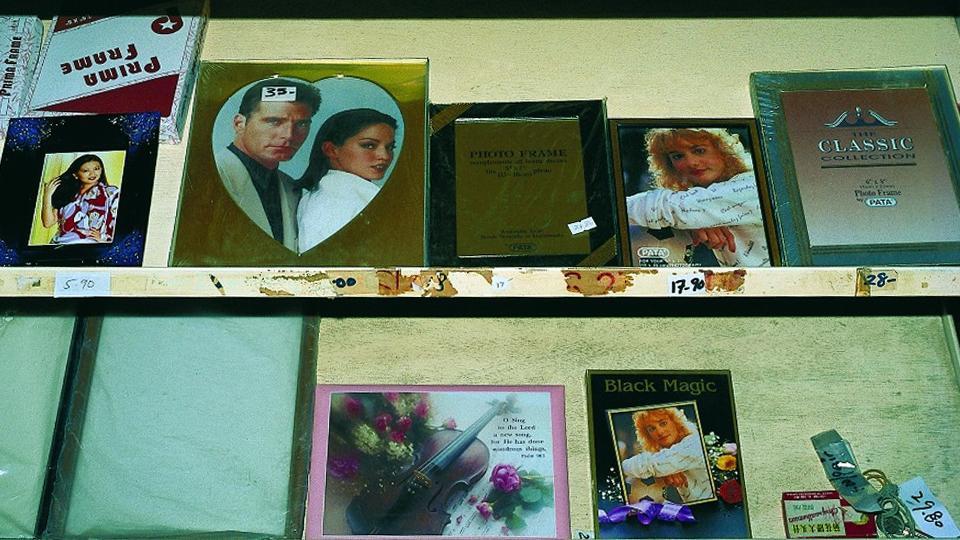

But what kinds of connections do they establish? They connect Clarinda and Voli with wider ‘worlds’ - with the ‘modern’ world of photography and photographic consumption - a world that is elsewhere and yet also here. A great many of the photographs that contemporary Roviana people possess come from elsewhere. It has been argued that photography itself is a central feature of modernity, a technology that fosters a specific set of attitudes towards the world. Given the relatively small Roviana population, and bearing in mind the way that Pierre Bourdieu has written about the inhabitants of a small French village who declared that they had no need to photograph each other because “we’ve seen each other too many times already”, what is it that compels Roviana people to photograph themselves?