Externally-led transitional justice policies do not lead to post-conflict reconciliation, Western Balkans expert’s research shows

Primary page content

In a paper published this week in the International Journal of Transitional Justice, Goldsmiths, University of London’s Dr Jasna Dragovic-Soso analyses why a decade of attempts to create a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Bosnia and Herzegovina have failed.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia building, The Hague. Photo by Julian Nitzsche via Creative Commons

While several initiatives were launched between 1996 – 2007, none came to fruition despite the considerable efforts of external actors.

Dr Dragovic-Soso, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, explains how the project foundered for three principal reasons: domestic political resistance, institutional rivalry between the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the Truth and Reconciliation project, and the project’s lack of legitimacy, notably among Bosnia’s victim associations.

This ‘history of failure’ in Bosnia holds important lessons for on-going truth-seeking attempts in the region and beyond, and highlights problems that arise in post-conflict societies when there is a high level of international involvement.

“In divided states, a national truth commission can materialise as a legitimate force for change only as part of a wider agenda pursued by leaders who genuinely embrace social and political reconstruction. External actors can support such individuals, but they cannot replace them," Dr Dragovic-Soso explains.

“Far from being a technical exercise, establishing a truth commission raises questions about legitimate authority in defining the past, the purpose of the reckoning and the thorny dilemmas of practical viability and sources of support.

“In this context, international actors are often not ‘external’ but integral to the process, seeking to create preferences and determine outcomes in line with their own interests and ideas.

“Their emphasis on the state and its institutions, on promoting nation-building and an internationally brokered political compromise, as was the case in Bosnia, may not always represent the most productive way of confronting a difficult and contested past or addressing the needs of those who suffered the most.”

"Confirmation of the country's deep ideological and political divisions"

Also published this week is a special open access edition of the journal East European Politics, highlighting Dr Dragovic-Soso’s research on Serbia’s apology for the Srebrenica massacre.

Her work explores how Serbia’s parliamentary debate of 2010 - which led to an apology for Serbia’s role in the 1995 massacre by Bosnian Serb forces of some 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men – did not represent a turning point in Serbia’s process of confronting the past.

In the paper, originally published in 2012, she argues that the debate and the ensuing parliamentary declaration instead confirmed the country’s deep ideological and political divisions.

It was an apology issued under pressure from the European Union, and not a result of any genuine political reckoning with the crimes of the Milošević era, Dr Dragovic-Soso argues.

The case is a key example of the limitations of external intervention in processes of acknowledgement and memory construction, which may produce tangible results such as the extradition of war criminals or political declarations, but do not on their own lead to meaningful engagement with a difficult past.

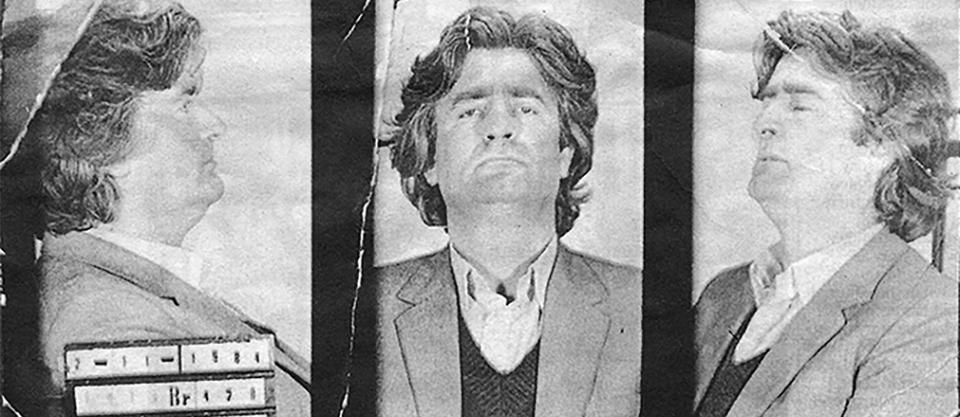

(Photograph taken upon Karadžić's arrest in November 1984)

"Real reckoning with a difficult past cannot be orchestrated from outside"

Dr Dragovic-Soso (Department of Politics) was recently interviewed by the BBC and wrote for The Conversation following the judgment of former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, and his sentencing to 40 years in prison for genocide and war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Discussing the Tribunal’s legacy, she notes both its successes in putting on trial some of the worst war criminals of the Yugoslav wars and its simultaneous failure to promote reconciliation in the region.

Reaching more than 32,000 people via The Conversation within a fortnight, the article quickly became one of the most read and commented-on opinion pieces published on the platform by a Goldsmiths author.

“Without international intervention there would probably have been little justice,” Dr Dragovic-Soso explains.

“However, the actions of external actors sometimes had counterproductive effects, undermining the reformist political forces seeking genuine change in their countries. And, ultimately, real reckoning with a difficult past cannot be orchestrated from outside.

If the Karadžić judgment is to have any longer-term resonance in the region, it will need to be part of a sustained internal and introspective process in those states where the crimes were perpetrated.

“That usually implies the presence of both genuine political commitment and a propitious socio-economic context. Unfortunately, neither of these conditions are on the horizon yet anywhere in the region.”