Goldsmiths History

For more than 200 years, generations of students have received an education here on the site of Goldsmiths.

In 1792 the Counter Hill Academy opened its doors in New Cross, in a house built by Deptford distiller, William Goodhew. The Royal Naval School then bought the site, building what is now our Richard Hoggart Building in 1843.

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths acquired the school and reopened it in 1891 as The Goldsmiths’ Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute. With the dawn of the twentieth century, the Company handed over the Institute to the University of London. It was re-christened Goldsmiths College and the modern era of Goldsmiths had begun.

Our roots – two centuries of educational legacy

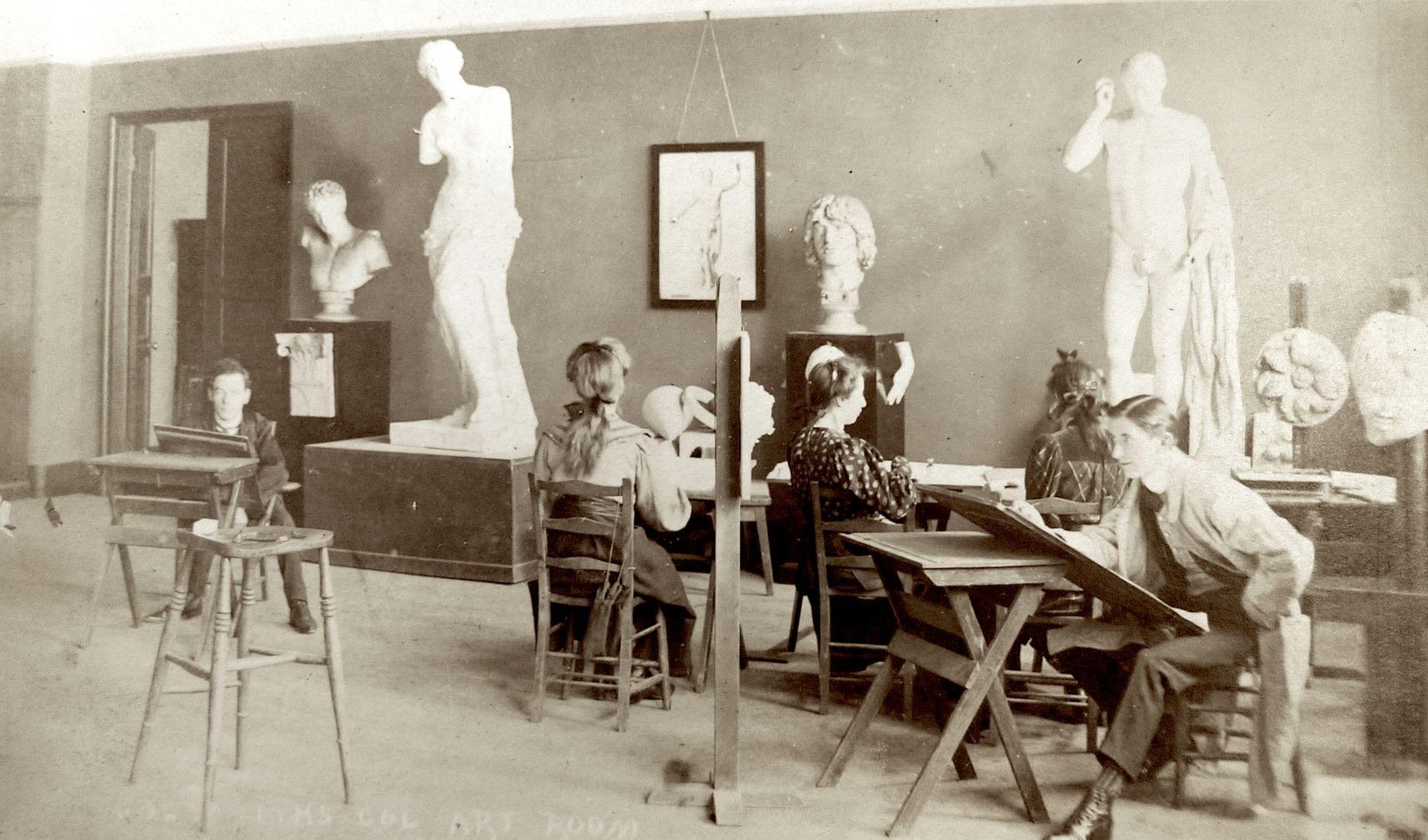

Goldsmiths Art students, 1908

The Counter Hill Academy, a private boarding school for boys, stood on the site of modern-day Goldsmiths from 1792 until 1838. After the Academy closed, the Royal Naval School bought the site. Over the next five decades they provided an education to the sons of officers in the Royal Navy and Royal Marines.

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, one of the most powerful of London’s ‘City Livery Companies’, purchased the site and buildings after the Naval School moved out in 1889. Two years later, The Goldsmiths’ Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute opened.

For 13 years, the Company ran a hugely successful operation. At its peak over 7,000 male and female students were enrolled, drawn from the ‘industrial and working classes’ of the New Cross area.

Our learning curve - how Goldsmiths’ academic portfolio has developed

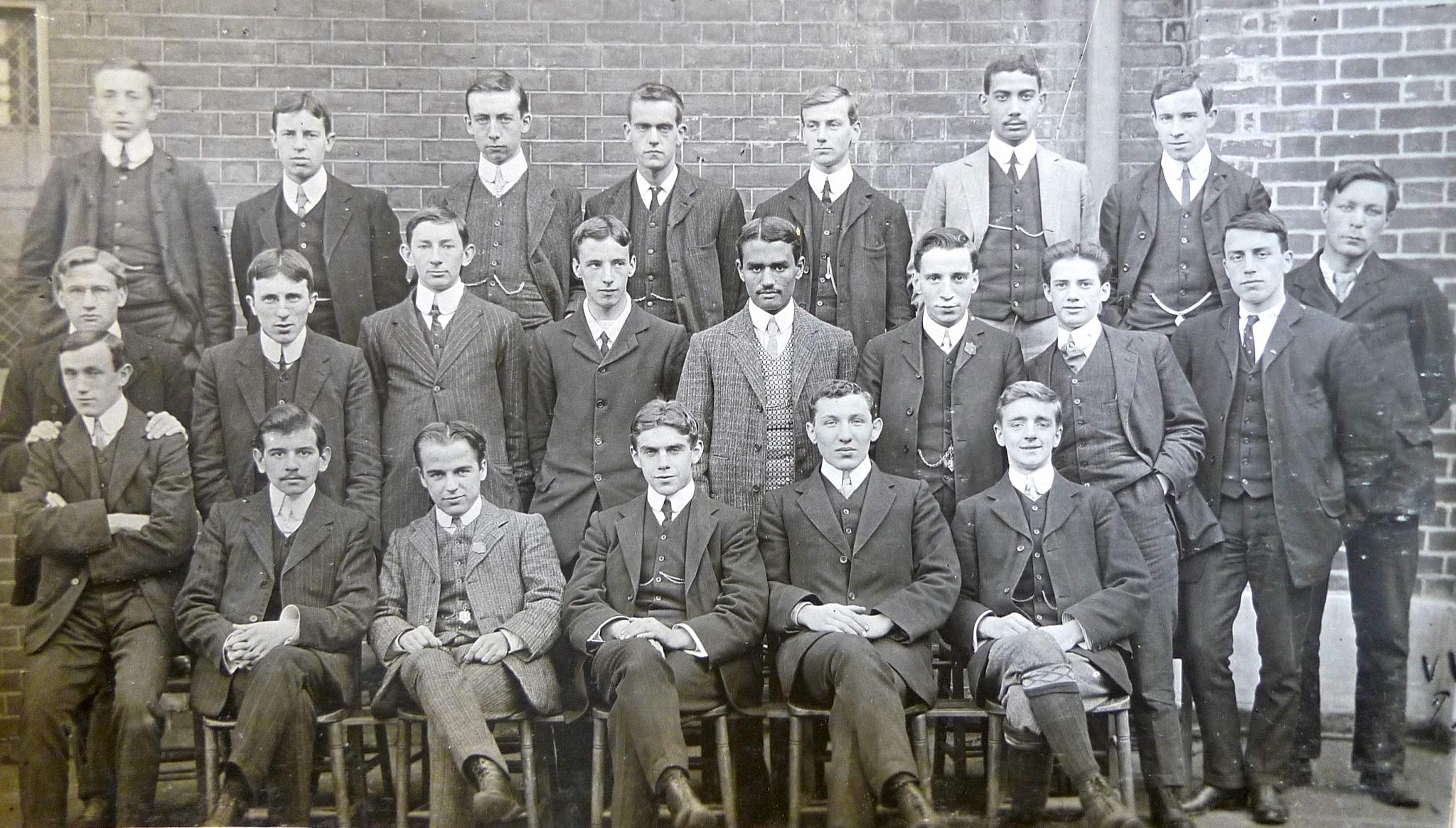

Trainee teachers at Goldsmiths in the early 1900s

The Technical and Recreative Institute offered a range of classes in the arts and sciences. Many of these led to City and Guilds or other awards. The Goldsmiths Company had established the School of Art as part of their Institute and continued to fund it after the College was created. The School began to shift focus towards fine arts, to distinguish itself from the trade and craft-based institutions found in London at the time.

At first, few art students sat exams or received any qualification at the end of their course. Nevertheless, the College produced many noted artists including the nationally recognised ‘Goldsmiths School’ of etchers, and the war artist Graham Sutherland. As the twentieth century progressed, art education became more academic. In 1904 the College became part of the prestigious University of London.

By the early 1960s, we were teaching highly respected Diploma courses in painting, sculpture and textiles. In the pre- and post-war years, the Goldsmiths’ Evening Department made up the other main part of the College. The Department offered predominantly non-vocational courses, maintaining the traditions of the original Goldsmiths Institute. The wide range of study on offer hinted at the explosion of choice in the decades to come.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s our portfolio of degree courses expanded as the number of students grew. Subjects that had been taught as part of teacher training evolved into degree programmes in their own right. By the start of the 1980s we were offering undergraduate and postgraduate studies across the arts and humanities, and student numbers had more than doubled.

The start of the 1990s saw Goldsmiths acquire its present status as a higher education institution. Her Majesty the Queen presented the College with a Royal Charter.

.png)

Cinematography students

In 2019 the QS World University Rankings recognised our world-leading status in the field of Arts and Humanities, placing Goldsmiths in the world’s top 100 institutions for these subjects. Goldsmiths came out in the top fifty worldwide for five of the academic subject areas covered in the rankings.

Today we actively encourage close links between our departments so students can learn in a fertile interdisciplinary atmosphere. This allows us to develop new programmes and new research opportunities that lead the way in contemporary academic thinking.

Our changing spaces - the buildings and physical spaces of Goldsmiths

College Green and the Grade II listed Richard Hoggart Building, c.1908.

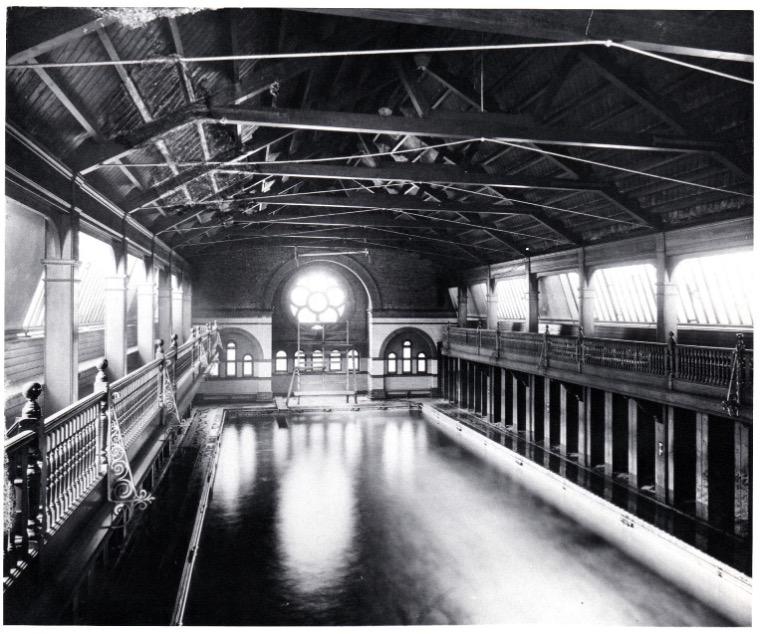

In 1843, the Royal Naval School commissioned the renowned Victorian architect Robert Shaw to design and build what has today become our Richard Hoggart Building. In the 1890s the Goldsmiths Company added a gymnasium, a concert hall and a swimming pool.

Shortly after the College was founded, the Goldsmiths Company provided funding for a new School of Art. This imposing building, opened in 1907, was designed by Sir Richard Blomfield - whose other main claim to fame was to design the now ubiquitous standard electricity pylon.

During the Second World War teacher training was relocated to University College, Nottingham. The students escaped the aerial blitz, but our college buildings did not. On 29 December 1940, incendiary bombs destroyed the roof, the library and much of the top floor of the Richard Hoggart Building. 1944 saw further damage and in May 1945 bombs completely destroyed the College’s swimming baths. College activities didn’t resume until the autumn term of 1946, but by May 1947 nearly all of the wartime damage had been repaired.

The College swimming pool in 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War

A busy period of development accompanied our expansion in the 1960s. We added the Whitehead, Lockwood and Education Buildings. We erected the Warmington Tower, built St James’s Hall, and added a new extension to the Richard Hoggart Building.

The Warmington Tower, an iconic 1960s building on campus

In 1998 we opened the Rutherford Building and it received a RIBA award as one of the 10 best new buildings in the capital. 2005 saw us open the eye-catching Ben Pimlott Building, a seven-story, purpose-built teaching space containing new art studios and lecture theatres, and providing accommodation for our psychology and digital media labs.

The striking Ben Pimlott Building opened in 2005

The Professor Stuart Hall Building followed in 2010, housing our Media, Communications and Cultural Studies Department and our Institute for Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship. The Professor Stuart Hall Building also gave us additional teaching rooms, meeting spaces, a new café and a new 250-seat lecture theatre.

In 2018 we opened the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art. Designed by Turner Prize-winning architects Assemble and housed in the Grade II-listed former Laurie Grove Baths, this free public gallery hosts a varied programme of shows, projects and residencies by national and international artists and curators, bringing world-class art to South East London.

The Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art

A history of recognising and nurturing talent

At Goldsmiths we aim to recognise and nurture talent. Nine of our alumni and staff have been Turner Prize winners and a further 24 have been shortlisted. Among these is Steve McQueen, the first Black director to win Best Picture Oscar for his 2014 film 12 Years A Slave.

2019 saw Bernardine Evaristo take home the Booker Prize for her novel Girl, Woman, Other, becoming the first Black woman to receive the prestigious literary award. Our former students are also among winners of the Mercury Music Prize, the Ivor Novello Award, BAFTA and many more.

In 2013 we established the Goldsmiths Prize to reward innovation in fiction. The inaugural prize went to Eimear McBride for her debut novel A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing. In 2019, Lucy Ellmann was awarded the prize for Ducks, Newburyport.

Lucy Ellmann wins the Goldsmiths Prize in 2019

Our place in the community

In 1891, when Goldsmiths Institute was established, its mission was ‘the promotion of the individual skill, general knowledge, health and wellbeing of young men and women belonging to the industrial, working and poorer classes’.

7,000 students were enrolled by 1900, attracted by a thriving recreational programme and the broad range of courses in craft skills, music, languages, art and sciences. Residents living in the cramped industrial districts around New Cross could enjoy rowing, rambling, swimming or tennis; and join the choir, the Camera Club or the Men’s or Women’s Literary Society.

In 1931, the College’s Evening Institute launched, bringing new impetus to our programme of extracurricular education. The Evening Department grew steadily, enrolling 1,400 in the last year of peacetime. After the war, the Department expanded, with 3,300 students enrolled by 1950. The Department’s objective, as stated in its 1956 prospectus was ‘to enable men and women to widen their knowledge and interests and enrich their leisure time’. The spirit of 1891 was very much alive at Goldsmiths.

Into the modern era, Goldsmiths remains committed to active involvement in community initiatives in New Cross and South East London. In 2019 we unveiled a community mural commemorating the 1977 Battle of Lewisham, following a collaborative project between Goldsmiths and local community groups.

In the same year, we worked with our partners Lewisham Council on a winning bid to make Lewisham a London Borough of Culture for 2021, rescheduled to 2022 as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 2021 Goldsmiths was the first university in London to launch a Civic University Agreement. Developed in partnership with 11 other local anchor institutions in the Borough of Lewisham, our Civic University Agreement commits us to working collectively to address some of the most pressing issues facing our local communities.

Community mural on the side of the Rutherford Building, commemorating the 1977 Battle of Lewisham