Call to halt Italy’s refugee return policies

Primary page content

Evidence compiled by a Goldsmiths, University of London research agency is being used to support legal action against Italy over the use of merchant ships to return refugees.

Captured migrants hiding in the hold of the Nivin. Photograph taken by the passengers using a mobile phone and sent to Informigrants.net.

Global Legal Action Network (GLAN) has made a legal submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee on behalf of an individual who was shot and removed from a migrant boat.

The legal action follows an in-depth investigation by Forensic Oceanography, part of the Forensic Architecture agency based at Goldsmiths.

The investigation focuses on the events of 7 November 2018 when the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre instructed a Panamanian merchant vessel, the Nivin, to rescue the occupants of an unseaworthy migrant boat and liaise with the Libyan Coast Guard.

Libyan officials then directed the Nivin towards Libya, where 93 captured passengers staged a stand-off, resisting illegal debarkation. After ten days, Libyan security forces removed people from the vessel using rubber and live bullets, and tear gas.

According to GLAN an individual was shot in the leg, arbitrarily detained, interrogated, beaten, subjected to forced labour and denied treatment for months.

GLAN lawyers argue that by using private seafarers to circumvent their obligations towards refugees, Italy and other states are acting in direct contravention of their human rights obligations. Private merchant vessels are used to return refugees to locations where they may suffer persecution and torture (refoulement), a violation under the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention Against Torture.

The Nivin Case, a report led by Forensic Oceanography’s Charles Heller, analysed multiple sources of evidence to offer a detailed reconstruction of the incident.

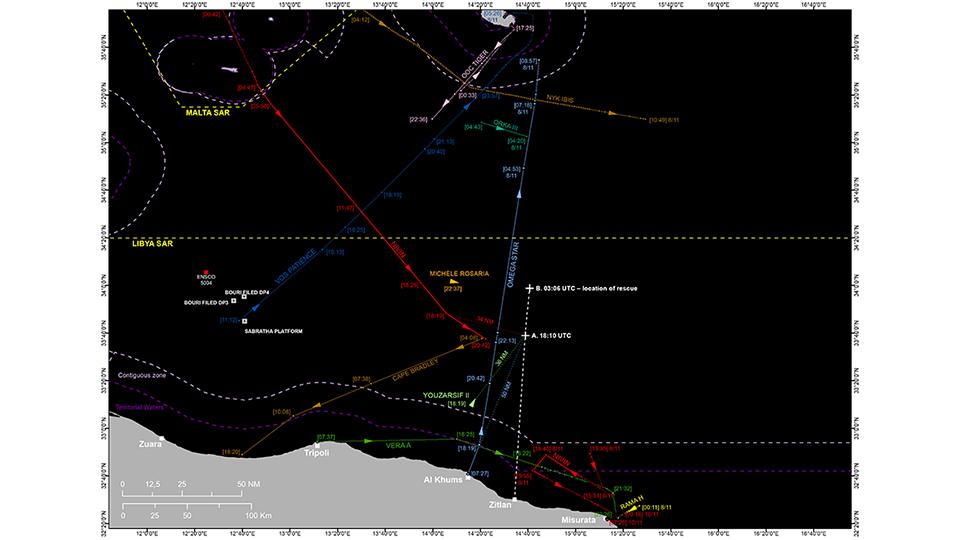

[Synthetic map of the Nivin incident on the basis of georeferenced positions and AIS data. Figure by Forensic Oceanography. GIS analysis by Rossana Padeletti. The map shows the 93 migrants’ boat trajectory as determined by two georeferenced positions, and the AIS tracks of vessels in the vicinity]

Using georeferenced positions and AIS tracking data, a digital reconstruction created a synthetic map of events and found the Nivin’s track interrupted at several points, suggesting that its AIS transponder was either not functioning or intentionally turned off. The investigation also found that despite the establishment of an EU-funded project implemented by Italy, Libyan Coast Guards lacked the communication equipment to contact and direct the Nivin.

Tracking data was cross-referenced with the testimonies of passengers; the reports of the WatchTheMed Alarm Phone, a civilian hotline supporting migrants crossing the sea; a report by the owner of the Nivin he shared with a civilian rescue organisation; the testimonies of MSF-France teams in Libya, an interview with a high-ranking Libyan coast guard official; limited official responses and leaked reports from EUNAVFOR MED (the EU’s anti-smuggling operation).

Charles Heller, co-founder of the Forensic Oceanography project, said: “We call upon Italy and the EU to immediately end their policy of refoulement by proxy, and cease implementing it either via the Libyan Coast Guard or merchant ships. Rescue activities must be used to save lives, not as a cover-up for border control. Italy should further end the criminalisation of rescue NGOs, whose humanitarian activities are partly filling the lethal rescue gap left by states.”

In May 2018, Forensic Oceanography published its Mare Clausum report, which demonstrated that Italy and the EU have implemented since 2016 a two-pronged strategy aimed at stemming migration across the Mediterranean. The strategy aimed to oust NGOs from the Mediterranean, and outsource border control to the Libyan Coast Guard. Due to the inability or unwillingness of the Coast Guard to search and rescue distressed migrant vessels, merchant ships have been called upon to fill the gap.

The Nivin Case demonstrates that privatised push-backs - where EU coastal states engage commercial ships to return refugees and other persons in need of protection to unsafe locations – have risen sharply since June 2018. The report digitally reconstructed the 13 privatised push-back attempts under the Mare Clausum strategy recorded between June 2018 – June 2019, a list that is likely to be incomplete. The outcome of these operations has been exacerbated by a closed-ports policy in Italy, which prevents ships that carried out rescue operations entering Italy’s waters to disembark rescuees.

Charles Heller said: “Our reconstruction has revealed that the outcome of the migrants being returned by the merchant ship depended on the migrants’ boat being initially sighted by a EUNAVFOR MED aircraft; the passing on of this information to Italian and Libyan coast guard authorities; the initial communication with the Nivin by the Italian coast guard ‘on behalf’ of its Libyan counter parts; and the later use of an Italian warship docked in Tripoli by the Libyan coast guard to contact and coordinate the merchant ship.

“Although the actors involved may give the impression of coordination between European state actors and the Libyan Coast Guard, control and coordination remained constantly within the firm hands of European - and in particular Italian - actors.”

‘THE NIVIN CASE: Migrants’ resistance to Italy’s strategy of privatized push-back’ by Charles Heller, Forensic Oceanography, was published on Wednesday 18 December 2019 and is available to read online