Meet the neuropsychologist opening the subject to all

Primary page content

Dr Ashok Jansari is a cognitive neuropsychologist and senior lecturer in psychology Goldsmiths, who has worked in the field for over 30 years and trained with experts all over the world.

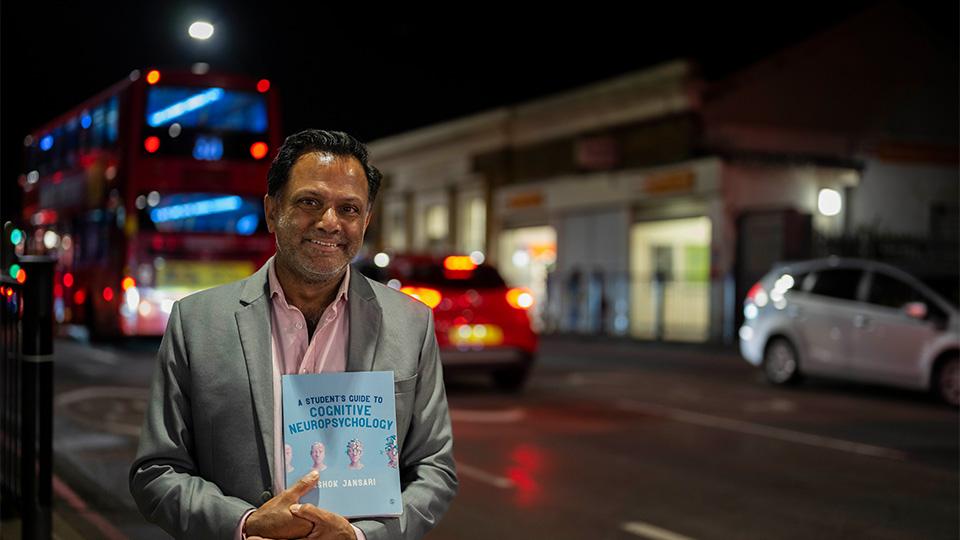

Ashok with his new book, A Student’s Guide to Cognitive Neuropsychology

Ashok believes that everyone will be affected by aspects of neuropsychology at some point in their lives, and he is passionate about educating the general public and making the subject more accessible.

As well as teaching at Goldsmiths, Ashok has hosted talks for the public during International Brain Awareness Week, spoken to national and international audiences through TV documentaries and inspired school students to consider perusing a career in neuropsychology.

Ashok recently published A Student’s Guide to Cognitive Neuropsychology, an informative and accessible text guide that helps readers understand traditional areas of cognitive neuropsychology, by applying core theoretical principles to real-world scenarios.

He has also created a series of free ‘Neuro Talk’ videos on his YouTube channel, where he draws on his years of expertise and provides a series of videos on topics from memory problems to the importance of sleep for the brain.

We sat down with Ashok to find out more about cognitive neuropsychology and why understanding the subject is so important now.

Lizzie Ellis: You have worked in the field of cognitive neuropsychology for over 30 years, how does your textbook help to convey your expertise?

Ashok Jansari: I have acquired a good depth of knowledge across the spectrum of areas within cognitive neuropsychology throughout my career. As an undergraduate student, I was mentored by a remarkable neuropsychologist, Dr Rosaleen McCarthy. Ros’s passion for working in lots of different areas rather than one (the usual academic method!) seemed to infect me. As a result, my PhD was on memory and amnesia after which I did a postdoctoral fellowship in the States with important neuroscientists.

I have also worked in the intriguing field of synaesthesia whereby individuals experience multi-sensory perception and have worked closely with clinical neuropsychologists in a relatively new field of rehabilitation. Finally, I have worked on the committees of both the British Neuropsychological Society and the International Neuropsychological Society which has allowed me to find out more about other areas. This has meant that all of the chapters in the book are informed either by my own expertise or the expertise of those that I know.

LE: What does the book cover and how is your guide and teaching influenced by your own research?

AJ: My basic principle is taking people on a journey about what we need to survive on an everyday basis – we need to pay attention to what’s happening in the world around us, we need to be able to recognise objects and interact with them, we need to learn from previous experiences. We need to organise all the information around us and work out what to do next, and if we want to survive in a social world, we need to be able to communicate with others.

Each of these ‘needs’ has resulted in different abilities developing namely attention, object recognition, face recognition, executive functions and language. I have worked in a number of these areas and therefore both my teaching and the book are informed by this experience.

LE: What do you hope that students and readers will take away from the guide?

AJ: I want people to take away the intricate complexity of our everyday abilities – we take our memory, language, visual recognition and thinking processes so much for granted and yet these are all incredibly complicated functions, with this complexity only being revealed when there is some form of brain damage. By then looking at the consequences, we get to understand the plight of people who have had these unfortunate experiences; this itself will hopefully give students an awareness (and maybe empathy) for when they will be touched by it themselves because of it happening to a family member or friend.

The second thing is the principle of how these unfortunate situations provide an incredible window and tool for looking at our intact abilities; usually, our memory, recognition, and language work so well that we are clueless to their intricacy. Finally, a special chapter in this book is on rehabilitation; no other book at this level for students includes a section on how we have reached a point after a few decades in this field of being able to help people with brain damage to try to cope with and maybe even improve some of their lost abilities.

LE: How do you overcome teaching difficult topics and convey information in a way that is helpful to students learning?

AJ: One of the strongest analogies I use is the correspondence between a computer and human cognition. A computer has an input device (the keyboard), hardware (the physical machine), software and output (a screen on which its processing is displayed or an instruction to a printer to print a physical copy of what has been done). In human cognition, we have our five input devices (the five senses), the hardware (the physical brain) and the output (human behaviour by speech or action).

The pursuit of cognitive psychology is to try to understand the software of the brain which are the mental functions such as memory, language, object recognition, face recognition and decision-making; these allow us to see or hear things, understand them and then act on them. This ‘software’ is called cognition which has been written down onto the hardware of the brain through evolution; the pursuit of cognitive psychology is to try to ‘decode’ this natural software to see how memory, language, and recognition function.

In our field we study ‘the bugs’ in the programme that have brought about these conditions and effectively try to ‘backward engineer’ to understand the whole programme – study someone with amnesia to understand intact memory, someone with a speech problem to understand intact language. Using these analogies and giving very real-world examples has always helped me in bringing the field alive.

LE: Why do you think it's important to make neuropsychology accessible to all?

AJ: Ultimately, I feel that everyone will be affected by aspects of neuropsychology at some point in their lives even if they are not aware of it. For example, dementia diagnoses are increasing due to improved life expectancies around the world. Also, the rates of head injuries through car accidents or workplace incidents are increasing.

We are now beginning to understand that repetitive non-concussive head injuries through contact could be leading to a form of brain damage known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) with athletes in their 40s getting early onset dementia.

All these different impacts on the brain will result in difficulties with cognitive functions. Therefore, while the end of the last century resulted in a greater public awareness of mental health difficulties, I feel that it will be the case that a great understanding of the consequences of brain damage will be necessary for the coming decades.